By Shelley Grieshop

sgrieshop@dailystandard.com GENEVA, Ind. -- Bill Meyer shakes his head in disgust as he recalls the horrible smell of rotting bodies around him.

He was only about 13, young and alone that cold winter day as he escaped from the Nazi camp by hiding in a makeshift morgue.

"There was a stench in the air you could not imagine. If I moved, I would have been shot," he says in a thick Dutch accent.

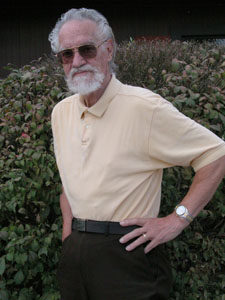

Meyer, 74, is a Holocaust survivor who kept his miraculous story to himself until a few years ago. Soon after going public with his horrendous account of the atrocities of the Holocaust era, he met Steven Spielberg and was interviewed by the production staff of "Schindler's List." The crew, at the time, were searching for authenticity in the making of the Academy Award-winning movie.

His heart-wrenching story also is chronicled at the Center for Holocaust & Humanity Education in Cincinnati, and it is the only one in the collection from a survivor still alive today. Meyer, who lives in Geneva, Ind. with his wife of 52 years, Josephina, will speak about his experience during an appearance in Celina this Sunday. See the informational box on back page.

He fidgets with a coffee cup in a little diner outside Geneva as he recounts his childhood, from a mischievous boy to a desperate young teenager whose life was saved by prostitutes.

His father, a policeman in Haarlam, Holland, married several times during Meyer's childhood; Meyer was the 17th of 18 children.

"I didn't like my father," he admits.

By age 6, food was scarce and Meyer was lured to a watch shop next door where he could get cookies from time to time. One of the store owners, Corrie ten Boom, took a liking to him and he endured her Bible readings to get the sought-after sweets.

Unknown to him initially, ten Boom ran an underground service to help Jews escape from the wrath of the Nazi Germans. Her family's efforts rescued more than 600 Jews, and their endeavors were made into the movie the "Hiding Place."

By the time he was 8, Meyer had become an accomplice.

"For 25 cents and cookies and milk I would run errands for Corrie," he says.

His father objected to his involvement "so I did it out of defiance," he says.

The Dutch people didn't care much for the Jews, but when the Germans rolled into town in 1940 and soon began publicly beating the Jewish men, women and children in the streets, mixed emotions emerged.

Ten Boom, a devout Christian, taught Meyer that Jews, too, were God's children and needed protection from the evil Germans. Meyer began delivering food ration cards, ID's, false passports and other items to Jews hiding all over the area. The blonde, blue-eyed boy was rarely questioned as he rode his bicycle throughout the countryside.

"I rode a bike without tires, only rims. I could hide things inside a sock or rag and stash it inside the rims. The Germans never looked," he says.

Many times Meyer was fed a hot meal at the end of his route and that was reward enough in hard times, he says.

Then one day he arrived back at the shop and was greeted by the Gestapo (Nazi police). Ten Boom had been arrested and some traitors turned in Meyer. Barely 13, he was thrown in jail after a beating. His father got him out but soon the Germans came looking for him and he was returned to jail.

"Then they shot my parents and seven of my brothers and sisters for retribution," he says, adding he still feels heavy guilt for their deaths.

He was sent to Vught Camp for political prisoners and spent nearly two years working at the camp.

"I kept thinking just one more day, just one more day. When someone got hung or shot, I was just grateful it wasn't me," he says.

In the winter, as temperatures dropped to 20 below zero, he wore only a thick shirt, pants and slippers, no socks. The stingy blanket on the cot he shared with five others, would move on its own from the crawling lice, he says.

Plagued with diarrhea from an awful diet, he feared he would be beaten to death. It was common for guards to be brutal when prisoners showed up at roll call with feces on their bodies. One cold morning, he made his move.

"I knew that every day they would take the dead out of the camp in a big cart to the pits outside the gate," he says.

After roll call, when the guards were distracted, he crawled beneath the stack of bodies and waited. He laid there all day "amid the slime and blood," he says.

At night, after the cart was dumped in the pit, he escaped to Rotterdam in the red light district of Holland to find his sister, Hanny. There he lived until the end of World War II. She was a prostitute -- a respected profession in that country, he says.

At the age of 14, he weighed just 45 pounds, he says.

In 1945, he was liberated by the Canadians and placed in a hospital where doctors slowly helped him gain weight. He later met and married his wife and moved the family to the U.S. in 1957.

Meyer says he witnessed so many horrors, such as German soldiers using men's testicles for shooting practice and the slamming of infants into cement walls in the streets. He has continuing health problems from his days as a prisoner and frequent nightmares.

Despite a warning from his doctor, the retired apartment manager continues to speak about the unspeakable, fearing the same mistakes will happen again if he is silent. His message is for the youths, the leaders of tomorrow, he says.

"When my generation is gone, there won't be anyone to tell these stories. Who did these things, these awful things? They were Christians. They were doctors, lawyers, they sang in church choirs. They left this happen, real people like you and me," he says. "And it can happen again." |