Thursday, April 14th, 2016

Drill prepares community for possible disaster

By Claire Giesige

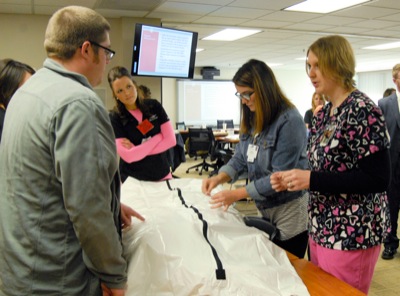

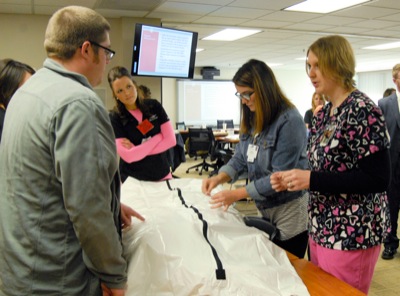

Photo by Claire Giesige/The Daily Standard

Mercer Health nursing supervisors work on tagging a CPR dummy during a mass-fatality drill. County officials gathered on Wednesday to run through a mass-fatality exercise, dealing with hypothetical crises such as supply shortages and hospital space limitations.

COLDWATER - "This is only a drill," Mercer County officials kept telling colleagues over the phone as they requested help in dealing with 41 fatalities in 48 hours.

Representatives from various Mercer County agencies and businesses attended a mass-fatality drill on Wednesday at Mercer County Community Hospital in Coldwater. Attendees included representatives from Mercer Health, which organized the event; Mercer County-Celina City Health Department; Red Cross; Celina Fire Department; Mercer County Sheriff's Department; Mercer County Emergency Management Agency; and the Mercer County commissioners. Representatives from area funeral and nursing homes also participated.

In the scenario outlined by the hospital's emergency department director Jenny Conn, county personnel were dealing with Day 14 of a Middle East Respiratory Syndrome outbreak in the area.

MERS was first reported in Saudi Arabia in 2012, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Those infected develop severe acute respiratory illness, including fever, cough and shortness of breath. About 3 to 4 out of every 10 cases are fatal.

In Wednesday's scenario, MERS had made its way to northwest Ohio.

"The grateful undead have risen," Conn announced at the start of the drill.

Fictional scuba divers had returned months previously from a trip to Indonesia, bringing the disease back to the U.S. One diver was a physician in Toledo. The physician had a fever and muscle aches but attributed them to fatigue from the trip and continued to practice medicine, spreading the disease to patients.

The drill began two weeks into the fictional outbreak, in which more than 200 MERS-related deaths had already occurred. Participants were instructed to treat it as a real-world crisis and respond accordingly.

The main issue topic was handling dead bodies. A funeral home representative said local funeral homes would likely be unable to handle that volume of deaths, meaning other storage places would be needed before burial.

Participants were quick to form an action plan. They decided the local Ohio Department of Transportation office would serve as a temporary morgue. First responders and medical personnel were instructed to double-bag bodies known or suspected of being infected with MERS to prevent further contamination.

As people table-hopped to brainstorm with other participants, resources were pooled and outside agencies were called to provide more body bags, medical equipment and even a mobile hospital. Non-MERS patients were diverted from Community Hospital, and a family-assistance center was assembled. Commissioner Jerry Laffin approved shutting down all large public events, and participants determined residents would be advised to stay home from work and school if feasible.

Businesses would not be ordered to close, Laffin and EMA director Mike Robbins said. Grocery stores likely would need to remain open, and businesses such as Celina Aluminum Precision Technology cannot easily shut down. Not only do employes handle molten aluminum with equipment that would take hours to shut down, but other Honda plants depend on their products.

Keeping patients' families informed and comforted would be another priority. A family-assistance program designed with counselors from Foundations in Celina was being called upon and the idea of electronic visitation through applications such as FaceTime was floated.

Burials also posed a challenge, particularly because family members' emotions would be running high. Because of the contamination threat from the bodies, embalming services and open casket funerals would be out of the question.

To deal with burials, officials decided funeral homes would orchestrate multiple same-day burials, limiting the services to immediate family members, who would likely have already been exposed. Ministers and counselors, as well as extra security, would deal with family members expected to become angry or overly emotional about the quick burials and closed caskets.

Mass burials would not be used, officials said, because of the long-term emotional distress it might cause to survivors left without a known grave of a loved one. Cemeteries have sections set aside for emergency burial situations such as this, officials said.

A grim question was posed - with limited resources, how would patients be prioritized for treatment?

Conn said in such a situation, the hospital would go to Crisis Standard of Care procedures, which essentially instruct medical personnel to focus on the people most likely to survive.

The drill ended with a reminder for participants to reach out at the first signs of a budding crisis and to keep open lines of communication.

"We do more drills than we're required to so we can practice and plan," Conn said. "We learn something new every time."