Saturday, December 2nd, 2017

Mercer County was hotbed of opposition to Civil War

By William Kincaid

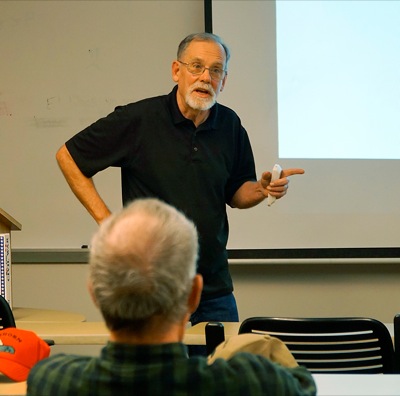

Photo by William Kincaid/The Daily Standard

Local historical researcher Harry Frech, who taught history and government at Parkway Local Schools for 29 years, speaks to a large gathering of Western Ohio Civil War Roundtable members at Wright State University-Lake Campus.

CELINA - Mercer County was once Ohio's largest bastion for Copperheads, Democrats who vehemently opposed the Civil War and called for an immediate peace settlement between the United and Confederate states.

Local historical researcher Harry Frech, who taught history and government at Parkway Local Schools for 29 years, on Thursday night presented his claims to a large gathering of Western Ohio Civil War Roundtable members at Wright State University-Lake Campus.

"History happens here. The Civil War happens here," Frech prefaced his talk.

Citing voting records and historical documentation of strong opposition to the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln and the draft as well as protection of deserters, Frech made the case that Mercer County was ground zero for Ohio Copperheads.

The Northern Democratic Party was split between the pro-war Democrats and the peace Democrats. Peace Democrats were known as Copperheads because they wore copper Liberty Head pennies as a badge, Frech said.

Generally speaking, the Copperhead movement attracted people with families or economic ties to the South and Irish and German Catholics, especially recent immigrants, Frech explained.

Many white northerners became enraged by Lincoln's Emancipation Proclamation, fearing a mass migration of freed blacks to the North, Frech said.

"Something else they seemed to be enraged about is the fact that now they're going to enlist African-Americans into the Army, and of course 180,000 of them are going to enlist," Frech said.

Further intensifying their rage, Frech noted, was the draft system in which rich men were able to buy a substitute to fight in their place, giving birth to such phrases as "a rich man's war, but a poor man's fight." Famous men who bought their way out of the war included tycoon Andrew Carnegie and future presidents Grover Cleveland and Chester A. Arthur, Frech said.

The 1864 presidential election pitted Democrat George B. McClellan against the incumbent Republican Lincoln. Lincoln would go on to win re-election easily. But in Ohio, Mercer County delivered one of the state's highest voter percentages to McClellan. In Gibson Township, McClellan took 161 votes to Lincoln's 2. Lincoln didn't get a single vote in Marion Township, Frech said.

Frech then pivoted to numerous displays in Mercer County of open hostility toward the war effort. In Coldwater, four young men given their draft notice broke into a woman's quilting bee, waving guns and saying they'd shoot it out with the Army and never be taken alive. Their gestures, though, proved to be hollow posturing. When troops arrived the next day, the young men fled before giving up and being arrested, Frech said.

Then there was Solomon Thompson, an Army deserter who went back to his family in Center Township. An Army lieutenant and two enlisted men were dispatched to escort Thompson back. When they had made it just past St. Marys, they were met by 17 men. The pro-Democrat Standard newspaper reported that those in the group were Thompson's friends while the Republican-leaning Van Wert Times Bulletin characterized them as Knights of the Golden Circle, the armed wing of the Copperhead movement.

Whoever they truly were, they opened fire on the three Army men. The soldiers survived but Thompson escaped, Frech said.

"The Army comes into the county afterward, though, and they arrest five men," Frech said. Again, the media coverage was polarized, with the Standard saying the five men were innocent while the Times Bulletin called them traitors.

Frech then pivoted to the story of Alexander Knapp of Fort Recovery. Knapp, Frech said, raised a company of volunteers in the Fort Recovery area. During a 1861-1862 campaign in Kentucky, a young black man named "Billy" crossed over to join the company, Frech said. Billy brought with him intelligence from the household of a Confederate colonel, including information about Confederate troop movement.

Once Knapp's company was ordered to march out, Knapp feared for the safety of Billy, upon whom the Confederate had placed a bounty, Frech said. Knapp wanted to bring Billy to Fort Recovery, but his proposal was met with overwhelming resistance.

"The people in Fort Recovery go crazy," Frech said. "They refuse this guy to go back into their community."

Appalled by the reaction, Knapp had published in the Standard a letter that tore into the community for not showing gratitude to a black man who had provided vital information to the volunteer company, Frech said.

Even before the Civil War, many people in Mercer County resented the presence of black men and women, many of whom began migrating here in the 1830s in search of cheap land and to escape the race riots of Cincinnati and other cities, Frech said.

John Randolph, a U.S. congressman from Virginia, owned a large plantation with more than 400 slaves, Frech said. Though Randolph advocated for slavery while in office, his will freed his own slaves upon his death. He bought 30,000 acres of land in Marion, Butler and Franklin townships on which he had ordered the construction of cabins for his freed slaves to live, according to Frech.

The freed slaves passed through Cincinnati before traveling up the Miami and Erie Canal. In New Bremen they were met by "a large mob of mainly Mercer County men stopping them from landing and driving them back down the canal," Frech claimed.

Delegates from all of Mercer County's townships held an informal convention and drew up a manifesto opposing any future black settlements, Frech said. The delegates organized an economic boycott against blacks that had a longtime effect on the county's demographics, he said. In 1850, Mercer County had the fourth-highest black populations among the state's counties. Blacks made up 20 percent of the Marion Township's population, Frech said.

But the black population began to decline after the boycott, and by 2000, Mercer County had the lowest percentage of black residents in Ohio, he said.