Saturday, January 27th, 2018

Readers share their stories

40th anniversary of the great blizzard of '78

By Sydney Albert

Submitted Photo

In this photo provided by Mandy Bertke, children take advantage of mountainous snow drifts for tubing and climbing in Burkettsville during the blizzard of '78.

On the 40th anniversary of the infamous blizzard of '78 - which some experts refer to as the "Storm of the Century" - many in Mercer and Auglaize counties still remember its disruptive power like it was yesterday.

Combined with a foot of snow already on the ground from previous snowfalls, the storm dropped another 13.2 inches of snow, and the wind speed broke records for January at 69 mph. Mountainous snow dunes formed, blocking roads and burying houses and businesses. Regular first responders couldn't reach many trapped in roadside vehicles or houses with no heat.

Single-digit temperatures created lethal wind chills, and 51 Ohioans died, including 70-year-old Reinhard Rain of New Knoxville who suffered a heart attack walking to a neighbor's home.

The 34.4 inches of snow that fell in January 1978 still remains the most snow ever measured in any single month.

Local residents had many stories to recount from the historic storm.

Shelter from the storm

The morning of the blizzard, Linda Zehringer was awoken by howling winds at 5 a.m., much earlier than she normally would have gotten up - and it's very lucky for her neighbor that she did.

"The wind was so loud, and so I got up to listen to the radio in the living room, and you would just hear horrendous stories on Portland's radio station," she said.

Zehringer remembers hearing stories of people trapped in cars on the roads, of people stuck in their freezing homes with no power. Then she heard something that gave her pause. It wasn't from the radio but outside her own home and very faint.

"I thought it was a cat or something at first," said Zehringer.

The more she listened, though, the more the sound started to sound like a human voice, like someone crying for "help, help." She had just gone to wake her husband, Ron, when she saw their neighbor, Babe Lamm, peering in through a bedroom window. She'd walked up and over the snowdrifts that had nearly covered the windows.

Lamm, who was 60 at the time, was Zehringer's mom's cousin. She had never gotten her driver's license, and each morning at 5 a.m., she would walk into Fort Recovery to open Thobe's restaurant for early customers. That morning Lamm had made it as far as her porch before realizing how bad the weather was, but when she had tried to go back inside, she couldn't find her keys.

By the time the Zehringers brought in Lamm, she was "cold and hysterical," barely able to walk. They helped her get warm and let her lie on the sofa to get her bearings - and an hour later, Lamm realized she'd had her keys on her the whole time.

Ron Zehringer was able to walk Lamm safely home later, but even so, Linda says it was lucky she'd gotten up to listen to the early news.

Blizzard baby

On Jan. 26, 1978, at about 9 a.m., the contractions started.

Marie Heitkamp was in labor at her home in Yorkshire, and one of the worst winter storms in recent memory was raging outside, dumping so much snow on the region that it would be days before some people were able to dig their way out of their homes.

The labor started mildly, but the contractions were coming about every eight to 10 minutes. At about 10 a.m., Marie Heitkamp's husband, Earl, called the hospital and was told the doctor wasn't in. However, he managed to reach the doctor at his house and was told they had four options: One, have a snowplow lead them to the hospital; two, have an emergency squad take them to the hospital; three, find a four-wheel drive vehicle and make the drive themselves; or four, have the baby at home.

By then, the snow outside was piled as high as the gutters on their house. The Heitkamps couldn't even get to the road, much less travel on it. They decided option four was their best bet, and the doctor concurred.

The next person they contacted was a neighbor, Ruth Oldiges, who lived just down the road. Oldiges was a nurse, and agreed to come help with the birth if she could get someone with a snowmobile to take her. They tried to contact John Seger, who worked for the fire department and they knew had a snowmobile but were initially unable to reach him. Oldiges called the Darke County Sheriff's Office, though, and Seger heard the dispatch on his pager.

The message was also heard across all other pagers and scanners in the area. Marie Heitkamp said that suddenly, "as if by magic," it seemed the entire community knew what was happening at the Heitkamp house. A citizens band radio base station "went crazy with the news."

The couple managed to talk with the fire department over CB radio and discouraged first responders from sending out the entire life squad to the house. As long as Oldiges made it, everything would be fine, they said. Seger packed an obstetrical kit and then picked up Oldiges at her house, 2 miles from the Heitkamp home.

Marie said that, as Seger tells it, the storm was so fierce, he tried to follow the power lines to keep from getting lost - no other good location markers were visible in the whiteout conditions. Fences were covered with snow, and even following the telephone poles, progress was slow. He kept losing sight of the lines and would have to wait until he could see them again before moving forward.

It took more than an hour to travel 2 miles in the storm. Seger and Oldiges arrived sometime after 11 a.m., and by then, Marie Heitkamp said, the contractions were getting worse. Seger was sent to the phone in the kitchen and was communicating with the Heitkamps' doctor while Earl Heitkamp occasionally relayed the progress from the bedroom. Finally, the doctor advised the father-to-be to stay in the bedroom until things were over. It was time.

Finally, at 3:26 p.m., the parents were able to hold baby Susan in their arms. Oldiges would later tell the Heitkamps that she had never delivered a baby before.

"Glad she didn't tell us that before," Marie Heitkamp said.

Seger and Oldiges were able to go back to their homes, but the work for Mom wasn't over.

"I couldn't rest like one would in the hospital," she said. "After about 3 hours I got up as we had a 13-month-old and a 4-year-old that needed attention, not to mention meals and housecleaning."

The couple was up around the clock for the next couple of days, taking care of three young children. On Sunday, when the winds finally died down, Marie Heitkamp's mother was transported by another snowmobile driver to their house, providing her daughter some extra help and giving her some much-needed sleep.

On Monday, the roads were cleared, and another neighbor, Larry Pleiman, opened up the Heitkamps' driveway with his tractor and loader. The couple was able to take Susan to the hospital to get a phenylketonuria test and silver nitrate drops in her eyes. Marie Heitkamp's mother was also able to go home, and afterward, the household went back to its normal routine.

The Heitkamps are thankful to this day for all the people who made food runs on snowmobiles and the calls of concern and encouragement. They also are thankful for Seger, who put his life on the line to drive in such severe weather.

"I don't know how many people when asked for the place of birth can say Yorkshire, Ohio, but our daughter can," Marie Heitkamp said.

Little Susan grew up healthy, and some may now know her as Susan Krieg, owner of The Pie Shell in New Bremen.

Rescuers rode snowmobiles

Volunteer snowmobilers rose to the challenge during the blizzard when roadways were choked with snow and ice and other forms of emergency response were unable to reach those in need.

"We knew we was going to get snow, but not like it was," said Larry Fennig, one such volunteer. "It was unreal."

Fennig was 26 at the time of the blizzard and worked at the old Huffy plant in Celina. He remembered the storm was so bad and the roads so impassable that regular work for him didn't resume for about a week. He was staying with his parents when, one morning, the sheriff called asking for help.

A group of people was trapped on State Route 29 between Harris and Riley roads. Fennig said a couple from Sidney had gotten trapped and called on a CB radio to a friend, who then also became trapped. The stranded travelers got in contact with a local CB radio group's members who tried to use four-wheel-drive vehicles in a rescue attempt, but their fuel lines froze while they were driving, and they, too, were trapped.

The sheriff called Fennig and Fennig's neighbors, the Bruns family, because he knew they had access to snowmobiles, which were the best bet for a successful rescue, so Fennig and Mike Bruns, then 17, ventured into the blizzard.

Bruns said as they drove out, he noticed the snowdrifts were already higher than an 8-foot fence surrounding an old lumberyard. The temperature was so cold and winds so strong that even through a scarf, Bruns ended up getting sever windburn on his neck. When they reached State Route 29, the two searched multiple cars stranded on the highway.

"The feeling that you have when you stop and you're walking up and you don't know whether you're going to find a person in the car, a dead person …" Fennig said, trailing off.

Fennig said their rescuees had heard the snowmobiles coming, though, and run out to meet them. They had all gathered in one vehicle that had been kept running. They occasionally got out to make sure the exhaust pipe was free of snow and ice. Fennig noticed that several of those who'd been stranded hadn't dressed properly for the weather.

Fennig and Bruns started by loading two people up on each snowmobile before starting back to Fennig's house, where his mother was making hot chocolate and his father was getting a fire started.

The way back was difficult. Fennig's machine was a smaller model, and three people were proving to be too much weight, causing him to keep getting stuck in the deep snow. Bruns said he didn't have that problem, but the whiteout conditions made it hard to see where he was going.

"I can remember driving up and down the highway and you couldn't see where Harris Road was. You couldn't see where to turn off the four-lane," said Bruns.

Eventually, after multiple trips, everybody was taken safely to the Fennig home, where they stayed for a few days until others could pick them up. But the work for Bruns and Fennig wasn't done.

"People would call the sheriff's department and then the sheriff's department would call our house to let us know what we could do to help people," Bruns said.

The day after rescuing the group from the highway, Fennig and Bruns' father, Dick, transported an 87-year-old woman from her home, which had lost power, to a neighbor's house with a firepit.

Fennig did other runs, transporting Dick VanTilburg, his wife and their three young children to a family member's house after they lost power and had no source of heat. He ran water to a farmer on Harris Road and his family took in the farmer's two young daughters when they lost power. He also transported milk from the farm to a small country store by Northmoor Golf Course. A few days after the blizzard, he was still going around town checking in on people to ensure they had everything they needed.

"During the blizzard, everyone was working together, and it wasn't for money. Money was never mentioned," Fennig said. "Money was not the object; you had to help people out."

Mike Bruns and his father would run medicine from pharmacies in town to people who needed it farther out in the country, and when they heard of neighbors who had run out of food, his mother would pack up food from their supplies to send to them. They would also stop at whatever grocery stores were open to pick up requested items.

"You know what the most requested thing for us to pick up was? Beer and cigarettes," Bruns said, laughing.

Though he and his father didn't bother looking for those, he said milk and eggs were also very popular items, along with baby formula. Of course, they just couldn't help some people. The Brunses got a call about a farmer in Rockford who'd lost power and couldn't feed his cows, but there was nothing they could do for him and weren't sure if making the trip to Rockford was safe.

Dick Bruns once ended up driving a sick person to the hospital at night, and later the family loaned a few snowmobiles to the sheriff's office to use for the week, Mike Bruns said.

"We were just being good neighbors," he said.

Even now, 40 years later, though, Fennig said he can remember the blizzard like it was yesterday, describing the tall snow dunes as rollercoaster-like. Snow drifts were even with the eaves of a two-story barn owned by Austin Schneider, Bruns recalled.

Both men lived in ranch-style homes at the time, with snow so deep and so dense they could walk onto their roofs. Fennig was tempted to drive his snowmobile onto the roof, just to show it could be done, but his father argued against the idea. Even when you're 26, Fennig said, you should listen to your father. Bruns and his family had a similar idea that they were able to do: They rode sleds off the roof of their house.

Working in the blizzard

Many were unable to work for days after the blizzard with roadways blocked or cars buried in snow, but some either found a way or were called upon in hours of need.

Beverly Duff and her husband, Karl, once owned Mendon's Market, and despite being unable to drive, the two would walk down Main Street to open the store and allow nearby residents to pick up supplies.

Items such as eggs and milk were brought in on snowmobiles from local farmers. Dairy farmers otherwise would have had to dump their milk, Beverly Duff said. So long as people brought their own containers to be filled, they could take as much milk as they wanted free of charge. People would find whatever way they could to get there. Duff recalled one couple who traveled down the St. Marys River to pick up supplies because the roads were impassible.

The store had no power so the register wasn't working, but for most supplies other than milk, the Duffs kept a tally of who took what until things got back to normal. Beverly Duff said no one in the community had issues paying their dues afterward.

Mike Hemmelgarn worked at Charlie's Pastry Shop in Celina. Initially, he received a call from his boss saying the business was closed, but not long after, his boss called him back. The Mercer County sheriff needed food to feed those at the jail, and anybody who could come in to help bake was needed.

Getting to work wasn't easy at first. Though Hemmelgarn lived in Celina, he had to make it from Cheshire Circle across town to the store on Main Street. One co-worker who lived farther out in the country ended up sleeping in the bakery because he couldn't make it home, Hemmelgarn said.

The crew started out baking other types of food for the jail, but as supplies began to dwindle, they began to stick with basic bread, Hemmelgarn remembered. He said just as the shop started to run out of flour, the National Guard in St. Marys used snowmobiles to deliver more from a warehouse in New Bremen.

Bea Kriegel, who was in high school at the time, recalls being required to sleep at her place of work at Briarwood Village. No sooner had she heard over the radio that school was canceled, the phone rang. Her employer was calling to seek help. Regular shift workers couldn't get in due to all the snow, but a volunteer snowmobiler could transport Kriegel.

"I believe it was considered an emergency for me to go to work that day," Kriegel wrote in an email.

Hand-washing everything instead of using the easy, modern sterilizing system to which she was accustomed made the job seem endless, Kriegel wrote. Luckily, the kitchen's stove was gas, and could heat water to wash the dishes. At the end of the day, she and her co-workers found an available rehabilitation room and settled down on thin mats.

Joan Long of Rockford has worked as a nurse at the Laurels of Shane Hill for decades. The night of Jan. 24, 1978, Long started work at 11 p.m., and she recalled telling her co-workers they had to keep the door clear of snow or else they wouldn't be able to leave. By 3 a.m. Jan. 25, they were stuck inside, unable to push the door open due to the snow. A call went out to Long's supervisor, asking for help, but he couldn't make it a mile down the road before he had to turn back.

For the first 24 hours of the storm, Long didn't get any sleep. They'd lost power, and with no generators, the building had no heat. All residents were moved into the dining room to help conserve warmth, and one staffer wanted to try starting a fire - an idea Long quickly shot down.

"I said, 'The last thing we need is, what if the building catches fire and the fire department can't even reach us?' " Long said.

Many of the kitchen utensils were useless for food preparation, but Long remembered they had coffeepots that still worked and were used to heat soup. One resident who had fallen and broken his hip was later picked up by a helicopter that brought them bread and milk.

After five days, when the nursing home was finally dug out and Long was driven home, she recalled the snow was "as high as the trees."

Called to help

With state crews unable to make it to the countryside, local people with the proper equipment were called to help clear some of the major roads in the blizzard's wake.

Tom Smalley was a grain farmer, but he had a truck equipped with a snowplow and a snowblower, and that was exactly what the Ohio Department of Transportation needed.

An ODOT official called Smalley to ask if he and another local resident could open State Route 49 to State Route 29, and the pair headed south from Sipe Road. From there, the other man, whose name Smalley couldn't recall, went to Celina on State Route 29 and Smalley turned and went back up State Route 49, heading to State Route 707, where they two later met up again. Smalley said it took two straight days of around-the-clock work to clear the roads.

"Going down 707, that was bad. I can say we wasn't making much time," Smalley said, laughing.

They had no trouble finding the roads even buried under all the snow, but clearing them was rough, he said. Under all the snow was a layer of slick ice.

"It started raining that (first) night, then turned to ice and then it snowed on top of it. The traction wasn't very good," he recalled.

As the pair cleared the roads at all hours of the day and night, people who had been confined to their homes would hear them working and come out to ask if they needed anything. Smalley was clearing State Route 707 sometime after midnight and people living along the road would ask them to come inside and drink coffee.

"We didn't have time for that," he said, laughing.

After two days of work, they called him off on that Sunday only for the wind to start blowing again, sending snow back across the roadways they'd already cleared. They called him again to tell him to keep State Route 49 open from Chattanooga to Willshire.

"They had us running that Sunday night, and all night to keep that opened up."

Don't miss the photo album with more pictures than could fit in today's paper.

Submitted Photo

In this photo provided by Rosalyn Bruns, Jenni (Bruns) Jones, 3, rides through a cleared path in St. Henry.

Submitted Photo

Mark, Ron, Sharon and Jo Dues wave from the Dues farm on State Route 119 in St. Henry. Photo provided by Jo Schwieterman.

Submitted Photo

A boy stands on a snowdrift in Burkettsville. Photo provided by Mandy Bertke.

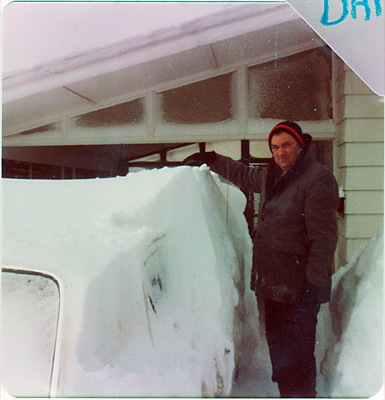

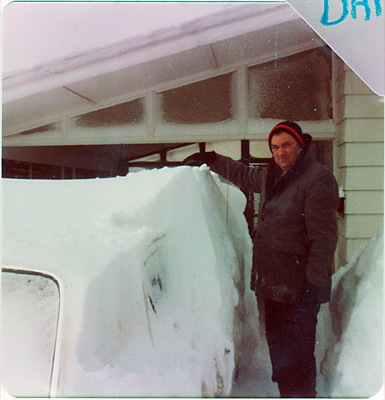

Submitted Photo

A man stands by a snowdrift. Photo provided by the Tebbe family.

Submitted Photo

Lana, TJ and Tom Smalley ride a snowmobile near the state line north of Chattanooga. Photo provided by Tom and Debbie Smalley.

Submitted Photo

A car belonging to the Bruns family is covered by snow in St. Henry. Photo provided by Rosalyn Bruns.

Submitted Photo

A man's car is buried in snow piled almost as tall as he is on Chestnut Street, Celina. Photo provided by Carol Zender.

Submitted Photo

Cars are buried in snow on the streets of Coldwater. Photo provided by Cindy (Knapke) Shaffer.

Submitted Photo

Grace Rutschilling and her family had to dig their way out of their Coldwater home after the blizzard. Photo provided by Grace Rutschilling.

Submitted Photo

Linda Shuster said snow blew in from a field behind her house on South Elm Street, Celina, creating snowpiles as high as the roofs of the houses. Photo provided by Linda Shuster.

Submitted Photo

This photo provided by Ron Krugh was taken along Sunset Drive in Mendon near Dick & Sons Funeral home.

Submitted Photo

Drifted snow buries a row of buses at West Elementary School in Celina. Photo provided by Carol Zender.

Submitted Photo

Snow is cleared off the road in Chattanooga. Photo provided by Tom and Debbie Smalley.

Submitted Photo

Tammy Romer stands atop the snow in Burkettsville as another child leaps from the pile. Photo provided by Mandy Bertke.

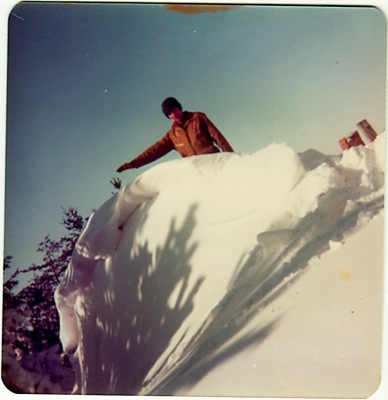

Submitted Photo

Using a snowdrift, two children are able to climb onto the roof of a farm building. Photo provided by the Tebbe family.

Submitted Photo

Doug Drexler shovels snow in Celina. Photo provided by the Drexler family.

Submitted Photo

A boy shows the height of a snowdrift. Photo provided by the Tebbe family.