Wednesday, April 1st, 2020

Ready for battle

Nurse on the front lines of virus fight in New Orleans

By William Kincaid

Submitted Photo

Versailles High School graduate and Premier Health X-ray technician Lauren Bohman returned to Yorkshire on Sunday after carrying out a travel assignment in New Orleans. The hospital where she worked was hit hard with coronavirus patients.

YORKSHIRE - Seeking out a new medical experience, Premier Health X-ray technician Lauren Bohman landed her first travel assignment in New Orleans.

Little did the 24-year-old Versailles High School graduate know her eight-week placement in The Big Easy's second-largest hospital would put her on the front line of a hellish, unfathomable pandemic with sickened patients descending upon the emergency room in droves.

"I went down there at the beginning of February, and I had no idea it was going to turn out the way it did," she said.

Bohman's last day on the job was Saturday. On Sunday, she packed up her things and drove back to her parents' home in Yorkshire. Her father, Dave Bohman, is originally from Osgood, and her mother, Mary Bruns Bohman, St. Henry.

Bohman, while in quarantine, recounted her harrowing experiences working in an urban hospital overwhelmed by a fast-moving contagion. Though she hasn't contracted the disease, she was intensely exposed to it while working 12-hour shifts in a ballooning hot spot. She's isolating herself for 14 days in accordance with a state mandate.

The last few weeks at the hospital, which she cannot name due to confidentially rules, had felt as if she were living in a movie, seeing many COVID-19 patients gasp for what would be their last breath, she said.

"It is crazy to see how fast this is taking over people's lives," she said. "This disease, it spreads fast, and when you get it, things can happen, change quickly."

Bohman was assigned to the hospital's emergency room. Coronavirus talk heated up three to four weeks ago, she said.

"It was the week after Mardi Gras … it started getting talked about a lot more," she said. "And then Thursday, March 12, was our first positive case we had come into the ER, and that's when it got real."

A man had tested negative for the flu but a week later had not improved. That's when his wife brought him to the emergency room. The next day he was on a ventilator in one of the hospital's overflow rooms that were last used after Hurricane Katrina in 2005, she said.

"He was a younger gentleman. He was 45 years old, healthy, a very well-known guy in the community, and just like that he was on life support," Bohman said.

In a week's time the number of incoming patients rose from just a handful to an overwhelming flow.

"Our hospital was maxed out with only COVID patients," she said. "Last week was really bad. We could not keep up. We were completely out of (personal protective equipment) some days, and it was very stressful."

The numbers continued to surge on Saturday, her last day of work. The emergency room has 45 beds.

"We had a waiting room completely full, and we had tents set up outside that could hold approximately 50 people. Everything was full," she said.

In fact, the hospital had reached its limit and would not accept any more patients, as ambulances were detoured to other local hospitals.

The facility was overwhelmed, to say the least.

"When I walked in on Saturday to go do my first rounds in the ER, to see one entire hallway with patients that had big flashing signs in red (over their rooms) that said DNR (do not resuscitate) - they were positive COVID patients - that was just a really defeated feeling," she said. "Those patients did not want put on a ventilator and actually several of them ... took their last breath before my shift was ever over."

COVID-19 test results take some time to come back. The next fastest way to see whether a patient likely has the disease is by X-ray, Bohman said.

"So we X-rayed every patient that came in the ER," she said. "By seeing the X-rays you can almost assume that they have it with what it looks like."

It looks like bilateral pneumonia but worse, Bohman said, adding it's hard to describe for someone not familiar with reading X-rays.

"Usually a good clear healthy set of lungs is nice and black and full of air," she said. "These lungs looked like somebody had smashed cotton balls all over them, and they were white, full of fluid. They're showing that the patient is drowning, basically. There's no lung capacity."

People ranging in age from 20 to 90 showed up at the hospital with the disease, Bohman said.

"I can't say it was ever really elderly. It was more middle aged. I would say ages 40 to 60," she replied when asked the most common demographic in the ER. "We have to help out in ICU a lot also, and a majority of the patients on ventilators were between 40 to 60."

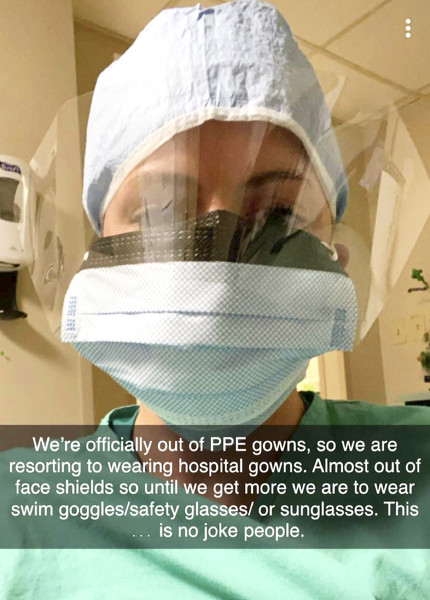

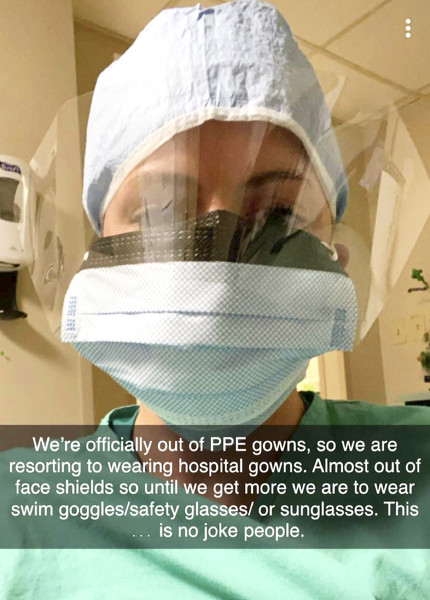

During the pandemic, hospital protocol for personal protective equipment began to change. Instead of wearing one mask a day, health officials were told to use one mask every five days, she said.

Staff were not permitted to wear handmade masks, Bohman said. The infectious disease control doctor did not feel those masks alone offered much protection against COVID-19.

"Now, we could use it as a protective covering over our mask, since we're wearing the same mask for five days," she added.

Medical gown supplies began to diminish as well.

"There was one gown that hung outside the patient's room and any staff member that went into that patient's room, all the staff shared that one gown," she said, noting it's stressful to put on such a gown not knowing if the previous employee had taken all the necessary precautions against contamination.

Health officials attempted to sterilize the gowns to reuse them.

"At one point we were trying to recycle the gowns and hang them up. Gowns are like napkins. They are paper-thin. They rip very easy. So that process did not work as well as planned," she said. "One day when we ran completely out of gowns, the health care workers were just wrapping themselves up in the gowns and ribbons that we provide for our patients to change into."

Bohman revealed her mindset going into to work each day.

"I was always questioning, 'Is this going to be the day I'm going to contract the virus? Is there going to be equipment for me to wear?' There were so many questions. Every day was a different day. I had no idea what to expect," she recalled.

None of her colleagues had to step out of the rotation due to infection.

"Thankfully, all my co-workers in ER, none of them have had to step out, yet," Bohman said. "(But) it's just a matter of time, especially with the PPE getting scarce as it is."

Near the end of her stay, Bohman said a downtown convention center was being repurposed into a medical isolation ward with 1,000 beds for COVID-19-positive people not requiring ventilators.

"(Officials) are bracing for (cases) to peak within the next week or two," she said.

Bohman works for Premiere Health, dividing her time between Miami Valley and Upper Valley hospitals.

"My travel agency is completely separate from the hospitals here," she said. "I signed up with a travel agency, just like a traveler nurse would, and they just kind of send you from spot to spot, wherever the need is."

This was her first traveling medical assignment.

"I signed up in January, and I got sent out in the beginning of February to go down to New Orleans," she said. "Young, single and I just wanted to travel. I never thought this would happen."

She's anxious to return to Premier Health once she leaves quarantine.

For the public, Bohman stressed the importance of handwashing and social distancing in protecting against the coronavirus. People must be vigilant for the virus' symptoms. Shortness of breath is a particularly critical symptom, she said.

"This past week we saw a lot of people who had tested positive earlier without coming to the ER and then they came once they had the shortness of breath," she said. "I hate to say it, but some of those patients were dead within … my 12-hour-shift."

As for health officials, Bohman recommended they wear personal protective gear when dealing with coronavirus-infected patients. They should also limit their interactions with such patients, as hard as that is to do as a health professional.