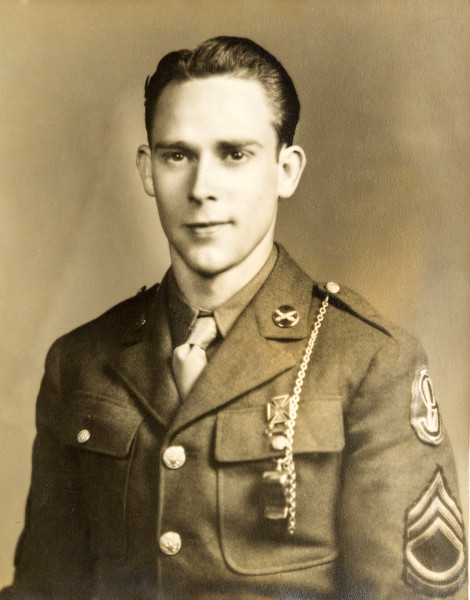

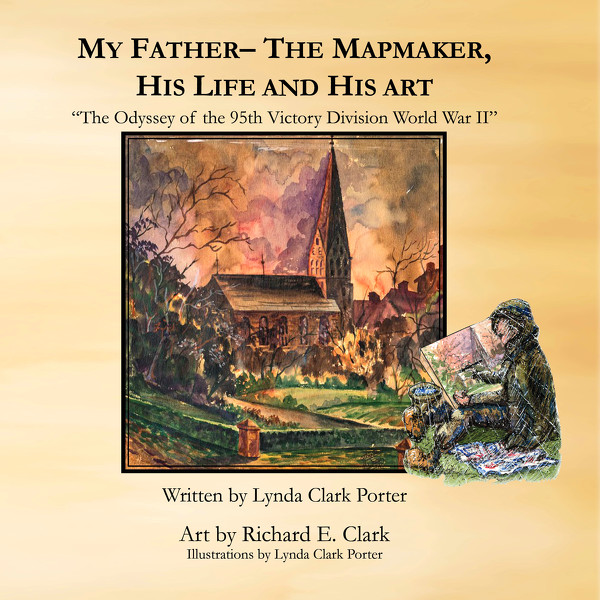

Richard E. Clark played a crucial role in World War II with the U.S. Army's 95th Infantry Division and is now the subject of the new book, "My Father - The Mapmaker, His Life and His Art: The Odyssey of the 95th Victory Division World War II," written by his daughter.

An American hero who played a crucial role in World War II with the U.S. Army's 95th Infantry Division - the legendary "Iron Men of Metz" - is the subject of a new book written by his daughter.

"My Father - The Mapmaker, His Life and His Art: The Odyssey of the 95th Victory Division World War II" chronicles the life of Richard E. Clark with a blend of history and Clark's own artworks, maps, sketches and speeches. It's told through the distinct voice of his daughter, Lynda C. Porter. Porter enjoyed a distinguished career as an art educator and worked for a period at Lima City Schools, before retiring and writing the book.

Aside from inhabiting a crucial position with the 95th Infantry Division, one that resulted in him receiving the Bronze Award for leadership in Lt. Gen. George Patton's victorious Battle of the Metz in 1944, Clark had ties to Celina.

Clark landed his first postwar teaching job at Celina City Schools.

"We believe that he would have started in the 1946-47 school year," Porter, who lives in southern California, said in a phone interview. "He lists his position as art supervisor."

While teaching in Celina, Richard Clark designed the nameplate for the The Daily Standard.

During his time in Celina, which Porter believes lasted about three years before he left for another job with Troy City Schools, he designed a nameplate for The Standard. Porter doesn't know the particulars of how he came to that assignment.

"He may have been doing some odd jobs on the side," she said, noting her father was an inventive, community-minded man, well versed in commercial design. "He knew how to design and do emblems and all of those kinds of things."

★ ★ ★

Clark was born in 1918 and lived in Caldwell in southeastern Ohio, not far from coal country. His father worked on the roads in Noble County and his mother was a homemaker, Porter said.

He was both ambitious and industrious from a young age, working a paper route and at a five-and-dime store to help keep the family afloat during the Depression and to save up money for college.

Clark's aptitude for leadership and art began to emerge in high school. He was student council president, a librarian and was involved with the yearbook commitee, the school newspaper and drama productions.

Known as the little guy - Porter likened his appearance to the TV character Deputy Sheriff Barney Fife (but much better looking) - Clark played on the school's basketball team and helped them win the state championship his senior year in 1935.

"I think my dad did discover that he had a talent," she said. "Back even in those days he created murals for the shops in Caldwell - which was set up on an old-fashioned square with a courthouse in the middle - that they would put up at Christmas time."

After graduating, he set out to become a commercial artist.

"As soon as he had earned enough money, he applied and got into the Cincinnati Art Academy," Porter said. "He made it through two years before he ran out of money."

Undeterred, Clark found a job at Athletic Specialty Company in Columbus, designing school emblems and lettering uniforms for high school, college and professional athletic teams, including the Cleveland Browns and Cincinnati Reds, Porter said.

While working, he looked into enrolling at Ohio State University.

"I think he knew by then he wanted to teach art," she noted, saying Clark at this point now had talent and professional experience under his belt. "He found that he could get a scholarship to Ohio State."

He snagged a working scholarship and was assigned to a dormitory.

"It was called the Stadium Club," she said. "Under the Ohio State Stadium, there were dormitories and he was able to live there. In order to be there he cleaned rooms, served meals, washed dishes, etc., and he said he could hear all the cheering and noise of the games above but he had to just listen because he couldn't afford to go to the games."

★ ★ ★

Richard Clark often sketched and painted local scenery and everyday life as he traveled throughout Europe. This is a typical English pub.

Clark also spent two years in ROTC, training in artillery, which would play a huge role in shaping his future.

Immediately after graduating in 1942, Clark was drafted into the United States Army, which put his teaching career on hold for four years, Porter said.

"He rose very quickly within his division," she said, adding he was placed in artillery. "The 95th Division at that point was a brand new division."

Clark indeed enjoyed a meteoric rise in rank, moving from buck private to master sergeant in a mere two months.

"He was the operations master sergeant of the headquarters with 20 officers," she said. "That was the highest rank you could achieve as an enlisted solider before being an officer. He was in charge of artillery operations and headquarters, he was in charge of making maps of enemy territory, plotting firing data and running the operations as a command center."

During the war, men in small planes would take aerial photos all over Europe and send them back to Clark, the mapmaker.

Clark would take the photos and assemble them into "a collage," which he used to "make the maps for the troops and for the movement of artillery," Porter said.

Decades later, Porter and her sister found a few copies of his maps, which served as significant guides for soldiers in the war, she said.

"Some of them are on canvas or oil cloth and they were done, I think, so that the soldiers folded them and carried them with them," she explained. "They had his signature stamped on them."

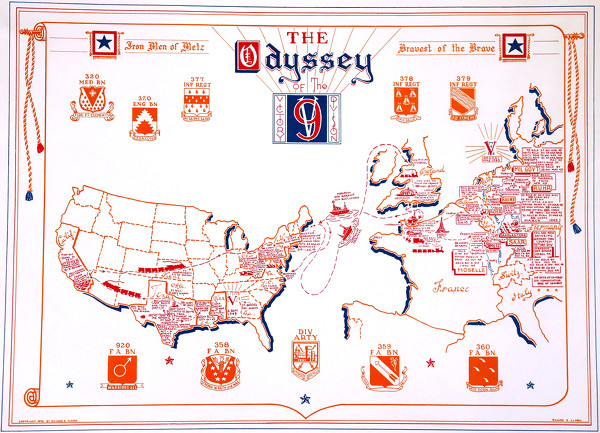

Richard Clark created "The Odyssey of the 95th Victory Division," a map that traces the 95th Infantry Division route through the United States and Europe and every major battle the 95th waged.

Clark was discharged from the service in October 1945. After getting married, he and his wife, Jessie, dedicated an entire year of their lives to completing an extraordinary mission - printing copies of a map entitled "The Odyssey of the 95th Victory Division" and getting them into the hands of the soldiers or their loved ones.

"He designed this large map which basically traces the entire route of the 95th Division through the United States, across the ocean, both there and back, every major battle and where they were in Europe and it's all illustrated," Porter said.

According to Porter, spouses, parents and loved ones were grateful to hear from Clark and his wife, as this often was the first communication they had after the war concerning their lost loved one. The map currently hangs in the 95th Division Museum near Oklahoma City, and appears on its website.

★ ★ ★

Clark then began his career as an art educator. Wherever it took him, Clark immersed himself in the local community by volunteering, particularly with the Lions Club, and giving public speeches at high school graduations, Memorial Day commemorations and other events.

"I think he learned a lot from the war, that he wanted to be involved in his community and his country and make a difference, to the point of probably being gone a lot," Porter said.

Porter recounted how her father's love of art permeated her childhood, as art supplies were always on hand in the home. She even got to study under him her senior year at Lima City Schools, where he was the art director.

"I basically learned how to do a thesis my senior year because we had to put together this huge report notebook that covered the world history of art," she said. "Both my sister and I went into art education."

Porter and her father's lives would cross paths again academically when she secured a teaching position at Lima City Schools.

"And here my dad was the art supervisor," she said. "One of my most special memories (was) he did come to observe a class of mine when I teaching. I had no idea he was going to come that day."

In trademark style - a twinkle in his eye and a wink - he said, "good lesson," she recounted.

"My Father - The Mapmaker, His Life and His Art" by Lynda Clark Porter, Raisykinder Publishing, paperback, 114 pages, $24.98 on Amazon.

After Clark died in 2003, Porter and her sister found a cache of her father's things - artworks, files, lectures, maps, outlines of speeches, journals, military histories, newsletters, etc.

"All of these things that we didn't know about," she said, adding her father while alive didn't often speak of his time in the U.S. Army.

She characterized the discovery of her father's personal materials as "the treasures of his life and the gold mines of mine."

The find, in part, spurred her to write an account of her father's life.