Saturday, August 29th, 2020

Starting a dialogue

Area activists say racism is real, seek understanding

Black Lives Matter

By Leslie Gartrell

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

Laina Williams and her husband, Domonique, play with their children, from left, Cayden, 8; Noah, 5; and Liam, 1, in the yard at their Mendon home. The couple decided to delay signing up Noah for preschool after a teacher said he would be the only black child in the class and could "teach the other kids culture."

CELINA - Kelsey Swann sat at a bar with friends a week after the first Black Lives Matter demonstration was held in late May in Celina.

Swann, who is biracial, said the first protest was phenomenal and she felt a connection to her community that she hadn't quite felt before. She was beaming as she spoke of the love and positivity she felt from the day's event.

A person she considered a close friend leaned over to talk to her over the noise of the bar.

"You're the only black person I like," he said.

In an instant, Swann said she felt like she was brought back to the reality of being a person of color in Mercer County. She was one of the "good ones," not to be thrown in with the "other" black people who supported the Black Lives Matter movement. She was the exception rather than the rule.

Since then, police violence and demonstrations against it have continued as unprecedented conversations about race have reached all corners of the U.S. However, local Black Lives Matter movement supporters have seen the community return to normal life. The group's call for the end of racially motivated violence and police brutality against black people largely remains unresolved. Its message sometimes has been lost in the political battle brewing amid a contentious election season and difficulty differentiating between the movement itself and the Black Lives Matter Global Network, an organization founded in 2013 after the shooting of Trayvon Martin, a black teen from Florida.

At 22, Celina resident Swann said she's tired. Tired of strangers touching her hair at bars without asking. Tired of saying "Black Lives Matter" isn't up for debate with people who are close to her and random people on Facebook alike. But it's a conversation she's willing to have over and over again until she sees change.

"I'm willing to stay this tired," she said. "I'm willing to stay exhausted. Other people my age are worried about when their next party is. I'm worried my dad is going to get killed."

The young Celina resident was an outspoken participant in the first protest, which was held outside the Mercer County Courthouse on May 31. Spearheaded by Mendon couple Laina and Domonique Williams, the first protest garnered hundreds of mostly white participants who marched through Celina's streets.

The Williamses said they were called to action in late May after the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor. Floyd was killed in Minneapolis in May after a police officer kneeled on his neck for nearly nine minutes, and Breonna Taylor was killed in March after being shot eight times by officers who burst into her Louisville home using a no-knock warrant.

They also felt pain from the death of Elijah McClain, a 23-year-old black man who died several days after being put into a neck hold by police and injected with the sedative ketamine a little more than a year ago in Denver.

Most recently, the shooting of Jacob Blake, a 29-year-old black father of six who was left paralyzed from the waist down after he was shot by police on Aug. 23 in Wisconsin, has reopened wounds still raw from the deaths of Floyd and Taylor.

Salt was poured in the wound when a white 17-year-old from a nearby Illinois community was arrested and charged with first-degree intentional homicide after shooting and killing two people after a Black Lives Matter protest demanding justice for Blake on Tuesday turned violent.

"It should have never happened like that," Domonique Williams said of Blake's shooting. "The cops giving (the teen shooter) water and stuff… it's overwhelming. It should have never happened in the first place"

The Williamses, who share children: Cayden, 8; Noah, 5; and Liam, 1, are familiar with racism. Domonique Williams, who is black, said it's not unusual for him to be followed around stores, whether it be by employees or shoppers, because of the color of his skin.

Laina Williams said the father of her oldest son, Cayden, has told her he'd "never let a black man" adopt his son, despite not being present in Cayden's life, and often uses racial slurs and derogatory terms when talking about Domonique Williams or other black men.

And when the Williamses went to register biracial son Noah for preschool last year, Laina said a teacher was excited because Noah would be the only black child in the class, and he could "teach the other kids culture." They decided to wait a year before signing him up again.

The two have said they're usually the quiet type who prefer staying in the back of the crowd rather than leading it. Yet with the support from friends and strangers alike, the couple decided to keep the ball rolling and create a Black Lives Matter Facebook group for Mercer County.

The couple created the group for Black Lives Matter events and discussions, and it has amassed nearly 300 members since early June.

In a county with a little more than 41,000 people, the majority of Mercer County is white. The Williamses expected more counterprotesters than supporters to show up to the first walk but were pleasantly surprised that roughly 200 people, most of whom were white, joined them on the steps of the courthouse.

Steve Klosterman of Celina, who is white, disagrees with the movement.

"For them to protest is just trying to stir up trouble to me," he said. "It's their right to protest, but I don't think there's a need in Mercer County."

The Williamses and Swann both mentioned they're often told that "it doesn't happen here." Teresa Wilson, 28, disagreed.

"People tend to think it doesn't happen here, but I'm a part of this community, and it's affected my life," said Wilson, who is biracial.

Wilson's earliest encounters with racism are ones she can't even remember. Her mother, who is white, was often asked if her daughter was adopted.

When she was 4, Wilson and her sister played a game of "slaves and master," where she and her biracial sister followed the orders of their white friend or got hit with sticks. On the first day of kindergarten she was told she didn't belong because she was black.

Perhaps most notably, Wilson remembers being chased down the street by a white man in his 20s, yelling slurs at her and her sister as they rode their bikes.

Teresa Wilson's father, Michael, remembers the incident well.

"Racism here is real," he said. "I told him 'If you ever call my girls that again, I'll finish you off.' "

Michael Wilson is protective of his children, and he came from a protective family as well. He moved to Mercer County from Cleveland in 1990 when he was 32. When he told his parents he'd be moving, his mother was worried for him, he said.

"My mom and dad had heard of Celina," Michael Wilson said. "My mom was terrified for me because it was a 'sundown town.'"

Sundown towns were communities throughout the U.S. that kept black people out by force, law or custom until the 1960s. Local historian Mary Ann Olding said while nothing official may have been on the books in Celina, black people knew to be out of town by sundown.

She said while black people would be welcome during the day, they would be pressured to leave by sunset. Instead, they would need to return to their homes or find lodging in St. Marys.

Michael Wilson said he's been told for years how much better things are now compared to 50 or 60 years ago. He doesn't quite see it that way.

"People have said things are better, but racism just took a different form," he said. "The blatancy has really come about the last three years. People aren't even trying to pretend any more."

The Black Lives Matter movement has spurred unprecedented conversations about race in cities and small towns since the early 2010s. Protests have emerged in cities and small towns over the course of several months in light of the deaths of Floyd and Taylor. However, like some protests for Floyd and Taylor, one in Wisconsin for Blake turned violent on Tuesday night.

"Good people don't do these things," Klosterman said of rioters at protests. "All of this violence and destruction is setting the wrong example for black kids. If (Black Lives Matter) wants to help black people, it needs to promote education and a strong work ethic."

Martin Luther King Jr. promoted non-violence as a civil rights leader, he said. However, Klosterman also voiced displeasure with the peaceful protests that took place in Mercer County.

"I drove by these protesters at the courthouse the other day," Klosterman wrote in a letter to the editor published June 17 after the second protest. "Instead of whining and complaining about how bad things are, they should try working 60 to 80 hours per week like a lot of us here in Mercer County do."

Michael Wilson said he didn't quite understand why some are so quick to bring up Martin Luther King Jr. when talking about the Black Lives Matter movement.

"What's the point of bringing up Martin Luther King Jr. when he still got shot?" he asked.

Teresa Wilson said the majority of Black Lives Matter supporters are nonviolent and don't promote or condone violence. While some may riot or loot, she said other members of the black community and Black Lives Matter supporters are using other tools to promote their message.

"I have the same anger and pain as those rioting and looting, but I'm trying to react to it differently," she said. "Some may kneel, some may write or create art, some might call their representatives.

"People are so reactive to buildings burning and broken windows. But as much as you're off-put by these things, are you as deeply off-put by injustice and brutality in black communities?"

Swann said she believes Black Lives Matter is about love and not putting one race above another.

"Black Lives Matter is love," she said. "The underlying message is that we want to be loved. We want to be able to go for jobs, sleep in our homes. We want to be able to do what everyone else can do without being hurt."

The Williamses said Black Lives Matter movement supporters are not default members of the Black Lives Matter Global Network, an organization founded in 2013 after the shooting of Trayvon Martin, a black teen from Florida.

"You don't have to support the organization to support the movement," Laina Williams said. "We're independent. I still think Black Lives Matter is a great movement, regardless of what other people think."

The Wilsons, the Williamses and Swann all agreed they wanted to educate and answer questions as much as possible when it comes to the Black Lives Matter movement. Promoting love, answering questions to which people genuinely want answers and preventing misinformation is the goal, according to the Williamses.

"I wish more (white people) would ask me questions," Michael Wilson said. "There's got to be a change in the way people think, period. Just because they have it good doesn't mean things aren't bad."

"Why would I put you down for wanting to support me?" Swann said. "The conversation will be uncomfortable on the end of the white person, but I want to get people out of their comfort zone. I'm praying there's a willingness to learn."

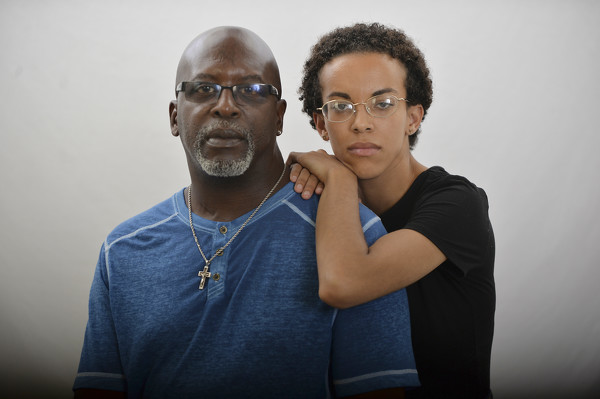

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

Kelsey Swann, 22, Celina, has felt the effects of racism since an early age while growing up in Mercer County. "You're the only black person I like," she was told in June by a person she considered a friend.

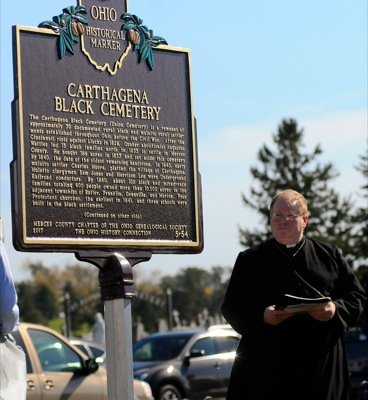

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

Mary Ann Olding, Fort Loramie, has chronicled black history in Mercer County and played a key role in garnering an Ohio Historical Marker for the Carthagena Black Cemetery in 2018.

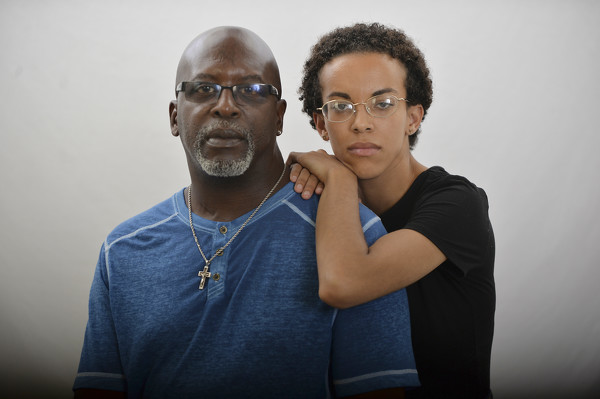

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

Michael Wilson, 62, remembers the time daughter Teresa, 28, faced racism firsthand when she came home from a day of playing "slaves and master" with a neighborhood friend.

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

A participant holding a sign joins a Black Lives Matter protest in Celina on May 31.

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

A group of people participates in a Black Lives Matter protest in front of the Mercer County Courthouse in Celina on May 31.