Tuesday, October 5th, 2021

Water Matters

Eliminating lead pipes will cost communities a fortune

By Sydney Albert

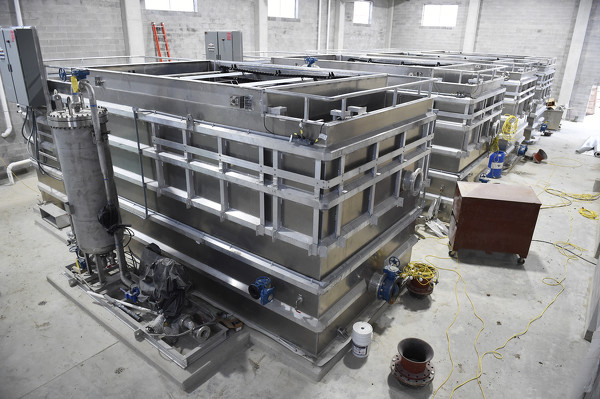

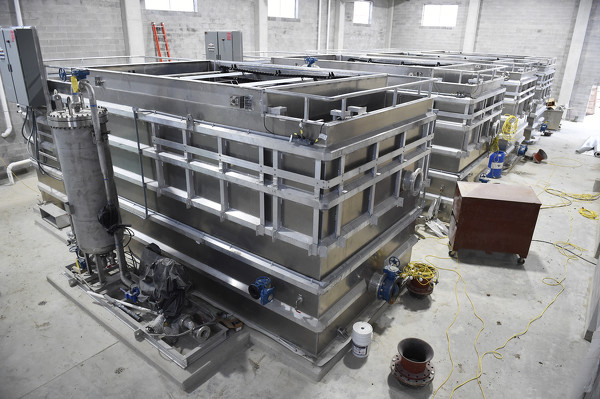

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

Four dissolved air flotation units were installed in January in the new addition at the Celina Water Treatment Plant. The units replaced outdated clarifiers and are more effective at treating raw water from Grand Lake.

The proposed infrastructure bill working its way through Congress could potentially open up billions of dollars for water and wastewater treatment projects around the nation, including sorely needed projects in our own backyard.

Several local municipalities are lining up for funds to assist with water and wastewater projects. On June 29, Ohio Gov Mike DeWine signed House Bill 168, which, among other things, invested $250 million to establish a water and sewer quality program administered by the Ohio Department of Development. The program provides grants to identify and invest in Ohio's most critical infrastructure needs.

The Daily Standard has spent months examining some of the area's infrastructure and interviewed officials on roads and bridges, local water systems and public school buildings. The news is both good and bad.

Almost every city and village employee interviewed mentioned work they needed or wanted to see completed, with varying degrees of urgency. Several mentioned wanting to replace aging water mains and pipelines. Others would fix inflow and infiltration of storm and groundwater, an issue that can lead to flooding in homes and towns during major rain events. Some said major expansions or upgrades would be required in the future due to regulatory changes. The estimated cost for projects ranged from a little more than $100,000 to $12 million.

Other potential funding options exist for such work, including low-interest public loans through the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency and grants from the Ohio Public Works Commission and Ohio Department of Development. However, many officials said they wanted to avoid taking out loans if possible.

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

St. Marys Water and Sewer Superintendent Jeff Thompson explains the process used to treat the city's drinking water.

The new influx of grant money is the first St. Marys' water and sewer superintendent Jeff Thompson said he'd seen in 15-20 years. It's an opportunity few want to miss out on, but many were unsure how likely they were to receive aid.

"I know we all have projects we can do to better our systems," said Mendon utility superintendent Randy Severns.

Smaller communities need money to make improvements too, Severns said, but he felt the lion's share of the funding would be swallowed up by bigger cities.

Lead pipes

The issue of lead pipes in particular came to national attention after the events in Flint, Michigan, in 2014. After local leadership switched its water supply without applying corrosion inhibitors to the water, lead from aged pipes leached into the water supply and began to sicken people.

Despite growing concern, public officials insisted the water was safe, ultimately creating a public health crisis for the 100,000 residents of the city. Several local and state officials resigned after the truth came to light, and some faced charges including obstruction of justice, lying to investigators and involuntary manslaughter, as reported by the Associated Press.

Under an Ohio law enacted in June 2016, community public water systems were required to identify areas either known to contain or that likely contain lead service lines and to map the potential areas. Service lines are those that connect water mains to buildings, supplying fresh water. Water with high acidity or low mineral content is known to lead to corrosion of lead-based materials, according to the EPA. The maps, many submitted in 2017, are available for public view on the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency's website.

Some municipalities submitted maps indicating their area had no lead pipes or probable lead pipes. Others, including the city of Celina, showed blocks of areas where lead service lines likely were in use.

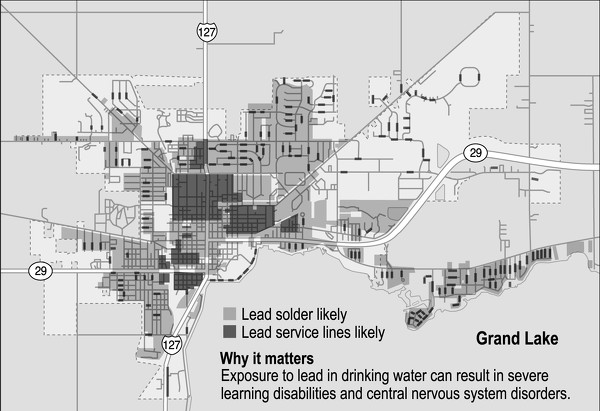

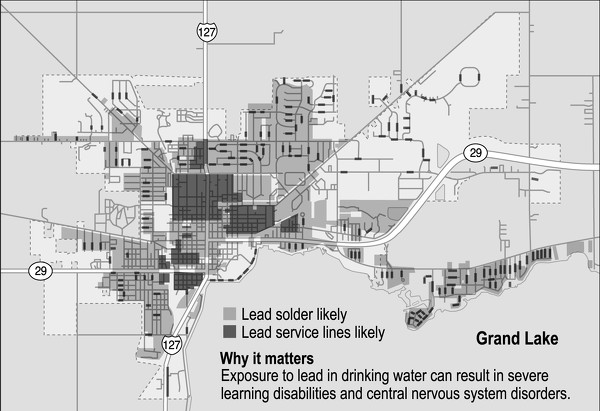

Photo by Bill Thornbro/The Daily Standard

Based on a 2017 map, lead service lines and solder were likely used in building these areas.

SOURCES: City of Celina, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Celina noted in its 2017 report to the OEPA that past water department records did not show when lead service lines were installed, repaired or replaced. The map indicated where lead service lines would have been installed based on construction dates and where lead solder would have been used. However, the report stated it has been practice to replace all lead found during water main replacement projects or repairs for the past 30 years or more. Several lead testing sites also are earmarked in the city's report to the EPA.

Mike Sudman, the city's water treatment plant and distribution superintendent, said while a majority of the city's main water lines have been upgraded in the last 20 years, locating and replacing lead pipes is part of an ongoing effort. The city tries to replace some every year, Sudman said.

If a resident knows they have lead service lines, they can contact the city and will be added to a list for removal, Sudman said. For those who are unsure, he recommended contacting Brookside Labs in New Bremen to have their water tested.

An online guide on the EPA's website shows how people can check their own home for lead pipes or fixtures by using a coin and a magnet. As a general rule, if a pipe or fixture appears to be made of metal, is easily scratched by a coin and magnets don't stick to it, it may be made of lead. The guide is available at

www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/protect-your-tap-quick-check-lead-0.

Officials in many local towns replaced old water mains and lines, lead or not, in the years since the maps were submitted, tackling the maintenance process gradually as part of street reconstruction projects.

Several village and city administrators and superintendents stated confidently that their communities had no lead water mains or pipes in use, at least on their end. They could not make guarantees on the fixtures and materials used in private homes or service lines that connect to city water lines.

Fort Recovery Village administrator Randy Diller said no public or private service lines were lead, to the best of the village's knowledge. All streets in the village have been worked on since 1986. Since then, all lead service pipelines found in that time were replaced with copper lines, he said. On streets that weren't completely reconstructed, lead lines had been replaced with copper either as a stand alone project or through the process of repair and maintenance, he said.

As for private service lines, Diller said that since 2011, village employees had visited every house and business in the village to replace water meters, at which time they checked the composition of private service lines. Anyone with lead pipes was required to replace service lines with copper or plastic ones.

Even for villages without lead pipes, though, various community officials said they'd like funding to replace leaking service lines and older water mains and service lines made of asbestos cement or brittle cast iron.

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

Pumps at the St. Marys Water Treatment Plant are used to convey treated drinking water to the city's distribution system for thousands of residents.

Wastewater requirements

Much of the more expensive work that needs to be completed in some communities involves wastewater systems.

The OEPA recently updated its requirements concerning ammonia, phosphorus and dissolved solid levels in wastewater, meaning some municipalities may need to complete expensive upgrades to their systems.

According to New Bremen village administrator Brent Richter, the EPA had once placed no limits on the amount of phosphorus and solids that could be released in the village's wastewater. At one time, ammonia limits were 2 kilograms per day in the summer and 13 kilograms per day in the winter.

The OEPA has since changed these requirements due to increased attention on water quality related to harmful algal blooms in Lake Erie and elsewhere. The village will be required to release no more than one kilogram of phosphorus per day, no more than 1,500 milligrams of solids per liter of water in a day, 1.3 kilograms of ammonia in the summer and 2.3 kilograms in the winter, Richter said. The new limits are lower than what the current lagoon system can attain, he said.

Every five years, the wastewater plant must renew its operation permit with the OEPA, and to continue operations, the village must comply. The OEPA originally gave New Bremen 36 months to come into compliance, but Richter said village officials continue to negotiate an extension.

What process the village will use to meet the requirements has yet to be determined, though the village currently has three estimates on possible solutions from consultants. The estimates range from $3.6 million to $12 million, Richter said.

By the end of this year or spring, Richter said he will have more information and upgrades soon will follow. The village would apply for as many grants and other funding sources for the project as possible, he said. The village also had considered a utility rate increase to help raise money for the potential work, but the decision was put on hold.

Other municipalities have taken note of the new OEPA limits on ammonia, phosphorus and dissolved solids in wastewater.

Many villages have lagoon systems, which generally rely on natural processes and microorganisms to eat away at solids and waste before the water is discharged into nearby creeks, rivers or canals.

Severns in Mendon and St. Henry Village Administrator Stanley Sutter were unsure what the future held. Both said an expansion or additional treatment would be needed to bring their towns' systems into compliance.

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

This Aug. 13 aerial photo shows the Minster Wastewater Treatment Plant.

The village of Minster utilizes an oxidation ditch system, in which wastewater comes in and is processed in a ditch which village administrator Don Harrod described as a circular race track. Water goes into the ditch, oxygen is added and waste settles to the bottom. The water then goes through an ultraviolet disinfection system which kills bacteria before it is released into the Miami-Erie Canal.

Though somewhat more advanced than a lagoon system, the village is still looking into ways to reduce dissolved solids to meet new OEPA standards. One option the village is considering is introducing more clean water into the wastewater treatment process, which Harrod said would help dilute the amount of dissolved solids.

Kerry Duncan, Celina's wastewater treatment plant superintendent, said he saw no need for any immediate changes to the city's process, as Celina already treats for phosphorus. The city has a conventional activated sludge plant; after initial screening, oxidation ditches are used for most of the biological treatment. From there, the wastewater goes through clarifier tanks which help settle the solids, is aerated and then disinfected by UV.

Any solids from the settling tanks go through further treatment to meet OEPA standards. After the sludge solids stabilize, they are dewatered. The dried solids can be sold to farmers, applied in fields or put in a landfill, Duncan said.

The city of St. Marys is designing a similar sludge press facility that could dewater solids at the city sewage plant and potentially save the city money in the long run, according to Thompson. While the design work is about $386,000, the full project could cost between $3.5 million and $4 million.

Aside from new regulations, wastewater systems are facing the problem of systems being clogged by "flushable" items. Coldwater administrator Eric Thomas said that while more products market themselves as flushable or disposable - and indeed, they are capable of getting through most toilets - the products create problems for municipal pumps.

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

In this Sept. 15 2020 photo, constructions continues on a multimillion project to replace clarifiers at Celina's water treatment plant. The new clarifiers are expected to remove almost all solids - including algae and other substances.

Influx and inflow

Depending on a community's size, wastewater systems can be built to handle anywhere from hundreds of thousands, to millions of gallons of water per day. When these systems exceed capacity, it can lead to backups and flooded basements.

Influx and inflow, often shortened to I&I, occurs when groundwater or stormwater and excess water from some homes find its way into the wastewater system. During significant rain events, I&I can push water systems beyond their limits.

On a normal day, Coldwater treats about 500,000 gallons of water, according to Thomas. During big rain events, flows can reach 3-4 million gallons, and direct inflow from down spouts, catch basins, pumps and more points of entry that shouldn't be able to flow into the system does, Thomas said.

The village has two water pumps that run every day and two larger pumps that come online during storm events. In cases where even the four pumps can't handle the extra inflow of water, an emergency pump kicks in to push water through the system and into a 30-acre pond, usually used as a polishing pond in the village's lagoon system. The village also has holding facilities that can store approximately 500,000 gallons which can be pumped out later.

Last year during a heavy deluge, the pumps couldn't handle the extra load, Thomas said. When that happens, water begins backing up in the lines and can come up through basements and toilets. Upgrades have been made since then, but even so, Thomas said he wasn't sure it would be enough to handle a similar flooding event.

Eliminating I&I has been a "constant crusade" for the village, and if the funds were available, Thomas said he would like to see more research done to discover exactly where the problem connections are. If possible, he said the village would probably hire an independent firm to inspect door to door. The inspections alone could cost between $100,000 to $200,000, he estimated; actually fixing the problems would be another more costly matter.

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

In this photo taken in January, construction was ongoing at the Celina Water Treatment Plant to convert an outdated clarifier into a bioreactor to reduce the toxicity of the sludge removed during the water treatment process.

Future growth

The American Society of Civil Engineers gives the country's water infrastructure a grade of C-, noting that the more than 2.2 million miles of underground drinking water pipes are "aging and underfunded." The group gave Ohio's water infrastructure a barely passable grade of D+ in 2021.

A D grade means infrastructure is in poor to fair condition and mostly below standard, with many parts approaching the end of their service life. A large portion of the system would exhibit significant deterioration, and condition and capacity would be of significant concern with strong risk of failure, according to the ASCE's 2021 report on Ohio.

While many large water utilities have made upgrades in recent years, the report states the upgrades were made "at the expense of Ohio's aging distribution networks." Most funding comes in the form of loans, which must be repaid through the water fee structure. During the past 20 years, Ohioans have paid water bills that have escalated at twice the rate of the Consumer Price Index, the report notes, with costs exacerbated by a general reduction in customer water use. These fee increases can hit low- or fixed-income customers the hardest, and even so, the need for asset renewal outpaces the ability to increase revenue through fees.

Ohio's wastewater systems received a grade of C-, with the ASCE again noting a need to repair, upgrade or replace old infrastructure.

The ASCE recommended establishing a water infrastructure trust fund to invest in critical infrastructure needs and minimize impacts on wastewater rates, which have increased by more than 70% in the last 10 years for the typical customer.

The ASCE also says customers can help keep costs down through at-home solutions, such as alternate disposal of flushable products and wipes.

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

Lime and soda ash are used to increase water pH and to soften the water at the St. Marys Water Treatment Plant.

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

Drinking water is treated inside the St. Marys Water Treatment Plant.

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

All water that flows through the city of St. Marys will first work its way through piping at the city's water treatment plant shown here.