Saturday, March 25th, 2023

Ex-NBA player talks drug dangers

By Tom Haines

Photo from Associated Press

Former NBA player Chris Herren (12), playing for the Boston Celtics, keeps the ball away from Charlotte's Eddie Robinson during a 2001 game.

MINSTER - The first time Chris Herren saw cocaine, he was an 18-year-old at Boston College coming back from a Sports Illustrated photo shoot.

The first time he saw OxyContin, a prescription opioid, he was standing on his front porch in his Massachusetts hometown after a successful rookie season as a point guard with the Denver Nuggets, just feet away from where his young son was watching cartoons.

Neither seemed like momentous occasions at the time, but his choice to try each of them led to years of addiction, unraveled his basketball career and brought his young family to the brink of collapse.

Herren shared his story earlier this week with a few dozen parents and community members in the Minster Elementary School gym as part of a tour of New Bremen, Fort Loramie, Marion Local, Minster, Russia and Versailles schools to educate local teenagers about the path to addiction and underlying self-esteem issues that can lead to it.

"The last 12 years, I've had the responsibility, I believe, as a father, walking into gyms like this and speaking in front of almost two million high school kids," Herren said. "And I truly believe in my heart I've made a difference for some of them."

"I do this for many reasons. One, when it comes to addiction, I think we've gone horribly wrong in the way we talk about it with our children," he continued. "I think we put way too much energy in the worst day and we forget about the first day."

When he was in high school in Fall River, Massachusetts, Herren was one of the top 20 high school basketball players in the country and a McDonald's All-American, even as he started following in his father's footsteps with alcohol.

His mother divorced his father shortly before he started college, so he decided to stay near home and enrolled at Boston College to study and play basketball despite interest from a number of powerhouse basketball programs. Within weeks of starting college, he returned to his dorm room to find his roommate and another student trying to hide a pile of cocaine.

At first, Herren said he turned away.

"As I'm walking through my dorm room, the little girl got up, grabbed me and said to me, 'It's okay. It's not going to kill you,'" he recalled.

He tasted it, then snorted a line of cocaine with the two of them.

"I told myself, 'I might as well try this once, get it over with,'" he said. "'I'll do this once, I'll never do it again.'"

Within four months of his first brush with cocaine, Herren failed three drug tests and was kicked out of Boston College, with his downfall headlining the Boston newspapers.

He got a second chance from Jerry Tarkinian at Fresno State and started to tap into his tremendous potential, highlighted by a 30-point game against top-ranked Duke on ESPN.

Coming back from that game, he went out to celebrate with his buddies, had a beer, and two hours later found himself doing cocaine again, Herren said. The next night, his trainer called and told him he'd been selected for a random drug test.

The next day, Herren admitted he would fail the test, and the Fresno State athletic director became the first person to tell him he had a drug addiction and tried to intervene, sending him to a 28-day rehab program.

After making it through rehab - still rationalizing that he wasn't the same as the other addicts - Herren returned to Fresno State and kept playing and kept getting high, while his wife was pregnant with their first son, he said. He managed to cope well enough to display his talent, and the Nuggets selected him in the 1998 NBA draft.

When he got to Denver, his teammates embraced him and told him that they weren't going to let him continue his drug habit. They told him there was no drinking on the team and they would randomly check on him on road trips.

"With those types of men in my life for the first time, that rookie season was the best I ever had on a basketball court," Herren said.

After the season, he went home to Fall River with his wife and young son. One night, a hometown friend knocked on the door, asked him to step out on the porch and showed him a bag of yellow pills: 40-milligram OxyContin.

Herren bought one for $20.

"I said, 'You should be ashamed of yourself, $20 for one pill?'" he said. "I threw it into my mouth, went back into the living room and finished watching cartoons with my son, having no idea that that decision, that pill, just changed all our lives forever."

By the time he returned to training camp four months later, he was spending $25,000 a month on his OxyContin habit and tried to detox on his own before the season. In the fifth day of withdrawal, he was traded to the Boston Celtics, his hometown team.

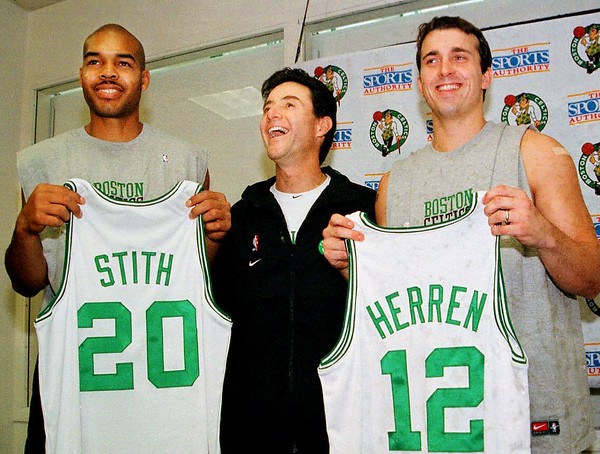

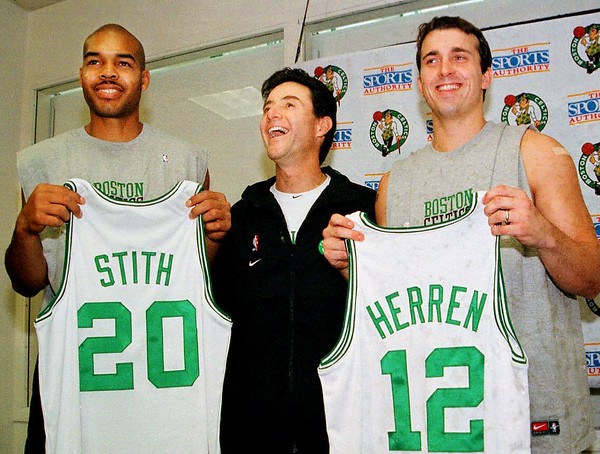

Photo from Associated Press

Chris Herren, right, poses with Boston teammate Bryan Stith, left, and head coach Rick Pitino during a 2000 press conference announcing both players had been traded to the Celtics by Denver.

Unable to handle the shame of relapse and the sickness of withdrawal, he called the friend with the OxyContin and asked him to meet him outside the Celtics' arena. Reporters surrounded his car when he arrived, so he couldn't get the drugs, and he struggled through the introductory press conference.

After one difficult year in which he was routinely buying pills outside the arena while wearing his uniform, the Celtics released him and he signed a deal to play in Italy.

He planned to cut back on the pills but ended up burning through his supply in three weeks. That's when Herren said he switched to heroin to manage the withdrawal.

Herren came back to Massachusetts and his career faded as his addiction continued. He overdosed for the first time a few months later in a Dunkin' Donuts parking lot and hit a woman with his car. Even as he switched primarily to alcohol, he overdosed three more times by the age of 32. The last time, he crashed his car into a cemetery.

One person after another stepped in to try to change the course of his life. The police officer who brought Herren to the hospital after he had crashed in the cemetery released him with a summons after telling him how much he'd looked up to him as a kid.

Photo by Tom Haines/The Daily Standard

Former NBA basketball player Chris Herren speaks on Wednesday at Minster Elementary School.

As Herren walked out of the hospital, a nurse who'd gone to high school with his mother stopped him, brought him back and called rehab facilities to try to find a spot for him.

Several days later, Herren got a call from Chris Mullin, a former NBA player and alcoholic he had stayed with while preparing for the draft. Mullin and his wife Liz had found him a spot at a rehab center and were paying for his treatment.

"'It's a gift from my family, hopefully to get your family back,'" Herren recalled Liz Mullin saying. "I hung up the phone, sat on the edge of my hospital bed and, by the grace of God, I took the Mullin family gift. I drove four hours to this treatment center I'd never heard of."

After a month at the rehab center, he left to be with his wife, who was alone and about to give birth to their third child. He arrived just in time, and his wife and 9-year-old son cried and told him that they missed and needed him.

Then he told his wife he was going for a walk.

"I wanted vodka," he said. "I wanted to shut the noise off. I promised myself that I would manage it, sip it, go through the day with it, but as soon as I tasted it, I chugged it. Thirty minutes later, I'm shooting heroin."

When he went back to the hospital the next morning, his wife and kids wanted nothing to do with him.

Herren went back to the treatment center, and his counselor told him to call his wife and tell her he would never contact her again, that she should tell their kids he died in a car accident. They would be better off, the counselor said, without a junkie for a father.

Herren didn't make the call. He tossed the cell phone back to the counselor and went back to his room.

"On what seemed to be the worst night of my life, I walked back to my room in that treatment center, I walked up to the edge of my bed, I started crying," he said. "I dropped to my knees and I started praying."

"August 1, 2008. By the grace of God, that's my sobriety date. I thank God every day for that man's words."

Herren's kids have grown up - his oldest son is 24, his daughter is 21 and his youngest son is 14 - and haven't touched alcohol or drugs.

But he said if he did catch his youngest son using alcohol or drugs, he would tell him he loved him and ask one question, which he urged all parents in similar situations to ask.

"Can you please just tell me why, buddy?" he said. "I need to know why my little guy needs to get wasted on a Friday night to hang out with kids he's known since kindergarten. Why can't you have fun just being yourself?"

Auglaize County Sheriff Michael Vorhees introduced Herren and talked about his own experiences in the Grand Lake Drug Task Force. He said when he started, heroin was the main issue in the Grand Lake area. But recently methamphetamine and fentanyl have become more prevalent.

Vorhees said much of the fentanyl coming into the area is in pill form and made to look like Percocet. Overdoses have occurred in New Bremen and Minster in recent years.

"We know the problem is here, we know the problem is real," he said. "We're not going to stop, as a drug task force or law enforcement. We say we're never going to win the fight, but we can win a lot of battles. And if we can win these little battles, save one life, that's what's important to us."