Ohio high school basketball games do not currently implement a shot clock. Could such a device be on the way?

When Parkway boys basketball coach Doug Hughes heard about a high school basketball game in Oklahoma that ended 4-2, his reaction was disbelief.

Hughes wasn't baffled so much about a team holding the ball to create such a low score, but that the other team would put up with it.

"You're not going to have a 4-2 game, because from a defensive standpoint, Parkway, we're not going to sit back and allow that to happen," Hughes said. "As I watch those stories unfold from around the country, I'm just scratching my head, saying, 'How can you allow that to happen?'"

On Feb. 8, Weatherford's 4-2 win over Anadarko in Oklahoma renewed debate on the merits of a shot clock in high school basketball, where such stall tactics have long been a part of the game. Three years ago in the district semifinals, Marion Local's Alex Eyink got the ball to start the second overtime, held it the entire period, then drove for a layup to beat New Bremen as time expired.

Minster boys coach Michael McClurg recalled a stall game from 1996 during his playing career at Versailles. Russia coach Paul Bremigan deployed a four-corners offense against the state-ranked Tigers, whose top player, Jason Turner, was out with an injury.

"Our second-best player, Dan Shardo, got in foul trouble, which just played right into their hands, our two best players out," McClurg said. "He got into foul trouble, sat the whole first half, and they dribbled the clock out. They did it from the start, but they got a little bit of a lead and just stayed with it."

Versailles took its second loss of the season, and McClurg remembered the final score being in the 20s.

When the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS) voted to allow shot clocks in high school basketball in 2021, nine states had already implemented them. Since then, only three more states have added a shot clock. Oklahoma's association in January voted 8-7 against adding a shot clock.

Ohio's most famous high school basketball alumnus, LeBron James, a little over a year ago tweeted support for a 35-second shot clock in Ohio, citing a better pace in his kids' games in California.

Ohio High School Athletic Association Media Relations Director Tim Stried said a shot clock proposal has never come to a vote and OHSAA is not considering one at the moment.

He doubts a majority of coaches would support one.

"The National Federation does allow states to use a shot clock if they so desire," Stried said. "In Ohio, we have not had the desire to have a shot clock, I can tell you that. Does it get discussed in circles surrounding high school basketball? Sure. But the OHSAA is currently not in favor of implementing a shot clock."

McClurg and Minster girls coach Mike Wiss said the Ohio High School Basketball Coaches Association included three or four questions about a shot clock in a 15-20 question survey earlier this month.

OHSBCA did not respond to a request for comment by press time.

NFHS recommends high school shot clocks be set at 35 seconds, which guarantees each team 27 possessions per game.

McClurg said the Wildcats averaged roughly 50 possessions per game this season. New Bremen boys coach Cory Stephens said the Cardinals averaged 0.97 points per possession and 56.7 points per game this season, for an average of 58 possessions per game. The longest possession he remembered was a little over 45 seconds.

Fort Recovery boys coach Bob Leverette recalled a game against St. Henry when he was an assistant under Jim Melton in which the Indians held the ball for four minutes at the end of the half. But all of the coaches interviewed said that few possessions currently last longer than 35 seconds.

Midwest Athletic Conference schools tend to be known for physical, man-to-man defense, and while Weatherford was content to sit back in a zone and allow Anadarko to stall, more aggressive defenses can spur action and punish timid offenses.

"There are teams that are known for having long possessions, but more and more you're also starting to see teams that have people get up into passing lanes, putting pressure on the ball to make the offense uncomfortable," Wiss said. "Those are things that we try to preach and teach. … That's kind of what this area's become. You've got to be able to handle pressure."

With area defenses often stronger than offenses, a faster tempo wouldn't guarantee higher scores. This season, with unlimited time to find shots, MAC boys teams shot 41.5%. MAC girls teams shot 34.1%.

In the Division IV girls regional semifinals in Vandalia, MAC co-champion Marion Local shot 28.8% in a loss to Tri-Village. The Patriots won by 12 points despite shooting 34.8% from the floor.

"You start running up against really good defenses," Wiss said. "Not saying people can't get shots off before a shot clock would sound, but your shots are defended much tougher. The games get more physical the further you run in the tournament."

If a shot clock was used, Hughes would consider running a token press to force an opposing team to take several seconds off the clock bringing the ball up the court. He also suggested switching defenses midway through a possession.

"Say we're sitting back in a 2-3 zone from the 35-second mark of the shot clock, when the possession started, 'til we get to the 17 second mark," he said. "At 17, we're going to go man-to-man. So we get them running their zone stuff, we match up, and now they've only got 15 seconds to get a shot off."

Leverette said with a shot clock, underdogs would have to rely on defense and time pressure to create an upset instead of holding the ball.

"Without a shot clock, that (weaker) team can hang around by holding the ball and playing really good defense," he said. "If there's a shot clock, for one, they've got to make that really good team run that shot clock down to the point where they have to take a tough shot at the end of the clock."

On the other end, a shot clock would likely eliminate a circle or continuous motion offense, where the idea is to run through the offense over and over until the defense breaks down. Instead, ball-screens and isolation plays might increase in order to get quicker looks.

Leverette and McClurg speculated that a shot clock might lead to more set plays. Stephens disagreed, saying that running more sets might make teams easier to prepare against.

"Currently, with all the good coaches out there and the scouting/preparing they do, you are lucky for a set to work more than once a game," he said. "With a shot clock, you might spend more time teaching players some actions and how to play, rather than running a set."

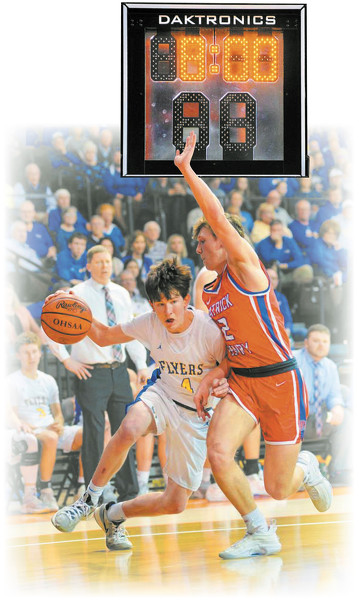

All of the coaches interviewed raised concerns over the logistics of implementing a shot clock. Every school would have to install clocks for whatever levels of competition were playing with them, down to junior high if necessary. Daktronics, one company that manufactures scoring equipment, gave an online quote of $4,139 for two standalone shot clocks and operating equipment.

Personnel, likely volunteers, would also be required to run the shot clocks during games. Hughes, who spent 11 years as athletic director at Parkway, said finding volunteers would be his top concern. McClurg pointed out that the scoreboards at Minster already require two operators.

For area schools, finding three volunteers to run clock for every basketball game could be a tall task.

"Being in a small school, I would make a big deal about the purchasing of them for every school in Ohio, as well as the people that have to run it," Wiss said. "Getting volunteers, that's not the easiest thing to do."

It also would be one more element for officials to keep track of during the game at a time when officials are becoming scarce.

But despite the logistical issues, Hughes predicted that Ohio will have a shot clock within five years, and Wiss and McClurg said it seems to be inevitable. Leverette, on the other hand, was skeptical that schools and coaches would ever approve it.

None of them expressed opposition from a basketball standpoint. Hughes and Wiss had no strong opinion, while Leverette and McClurg thought it would improve the game.

Beyond his opposition to stall ball and his own preference for an up-tempo game, McClurg predicted that high school players would be "a hundred percent" in favor of a faster pace.

"Every single one of them would rather play up tempo than sit there and not play - just guard, or even run an offense for two or three minutes straight," he said. "Every single one of them."