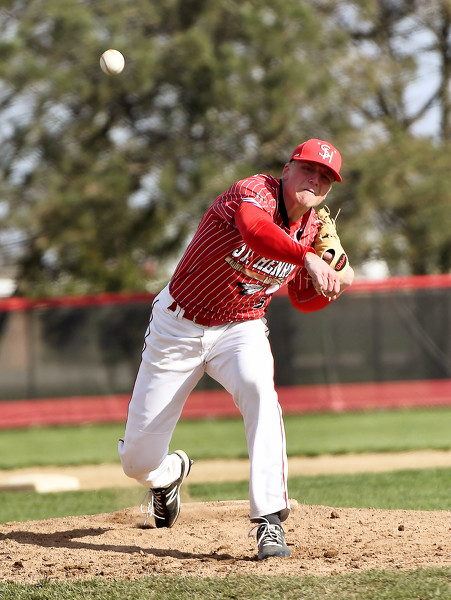

St. Henry alum Ryan Uhlenhake, seen here throwing for the school in 2021, hit 90 mph with his fastball before his senior year.

Looking back at his time as a catcher for St. Henry High School in the early 2000s, Mike Gast doesn't remember any of his teammates throwing much above 80 mph.

This past offseason, entering his third year as St. Henry's coach, Gast had six pitchers throwing at least 80 mph. Junior Lucas Clune hit 92 mph.

"Most of my coaching staff is alumni, and a lot of them were part of the '99 and 2000 state teams," Gast said. "They like to talk about, if they were hitting today, blah, blah, blah, and I joke with them that if they were hitting today, they'd be batting about .250.

"Coach Neil Schmitz was a very good high school pitcher and went to Bowling Green after high school to pitch but I'm not sure he ever threw any harder than 84, 85 in high school, which, today, we might see that once a week."

Velocity has been climbing at all levels of baseball, starting with Major League Baseball and trickling down. Wapakoneta High School graduate Brian Garman, the pitching coach of the Double-A Dayton Dragons, has three pitchers on his staff throwing 100 mph and two more at 98 mph. Ball State University, the alma mater of New Bremen coach Chad Wells, has had two 100-mph pitchers in recent years. Tom Held at Defiance High School has three pitchers in the 90s this season.

The jump has been more subtle in the Grand Lake area: Rather than eye-popping numbers at the top end, there have been more kids moving into the 80-mph range. Wright State University-Lake Campus interim coach John Bailey said when he joined as pitching coach in 2015, local high school teams might have one or two kids throwing in the 80s, and now they might have three or four.

"There's never been too many years where there aren't at least a couple kids who can run it up there in the mid to upper 80s in the (Midwest Athletic Conference)," Coldwater coach Cory Klenke concurred. "But I would say maybe teams' No. 2s, No. 3s or 4s, are improving velocity, improving on their pitching, continuing to get stronger."

"But I also think we know more, there's more out there," he added. "It's just a matter of if the coach and player and parents are willing to take the risk to possibly get there."

St. Henry third baseman-relief pitcher Bryce Brookhart works out with wrist weights at Wally Post Athletic Complex.

Gast asserts that the biggest change in high school pitching in the last 20 years has been the adoption of formal strength programs by baseball teams.

Gast played football and lifted weights in the fall, but there wasn't any assigned weight-room work in the spring.

"And I don't think I was in there real religiously during baseball season," he said.

Klenke said he first helped implement more baseball-specific lifting in the winter when he returned to Coldwater as an assistant under Brian Harlamert a decade ago. Other former pitchers, like Garman and Bailey, recall being discouraged from hitting the weight room.

"I was told, don't do certain stuff in the weight room as far as chest and arms," said Bailey, who pitched for Jay County in high school. "And that's actually completely wrong."

St. Henry graduate Ryan Uhlenhake, Gast's first 90-mph pitcher and now a sophomore at Indiana Tech, said that the most fundamental element of his 15-mph jump in velocity through high school was gaining strength.

"I used Garman's plan, really buckled down and focused in on it," Uhlenhake said. "It included a lot of deadlift, squats, bench press. And just at that point, I was super skinny, so it's all about adding muscle mass, eating a ton of food trying to gain the mass so I could gain the muscle to throw harder."

Gast, Klenke and Wells also noted that the spread of year-round weight training in basketball and football has made a difference for multi-sport athletes.

"The high school athlete in the last 10 to 15 years has become incredibly more athletic," Wells said. "And a lot of that has been a direct result of people finally seeing the benefits of gaining strength."

Plyo balls of different weights are used for overload-underload training, which helps pitchers gain velocity.

When Held graduated high school in 1980, he spent his time playing softball and throwing Nerf balls in a friend's garage. He played basketball in college, but in 1982, he went to a baseball tryout camp where his arm caught the attention of a scout with a radar gun.

A year later, he was drafted, and he went on to play three years of Minor League Baseball.

"It was a few years when it really clicked, and I go, 'You know what? I have a feeling that softball and throwing that overload or a heavy ball' - because a softball's 7 ounces, baseball's 5, and a tennis ball's about 3 - 'I think that might've had something to do with gaining arm strength,'" Held said.

Held, who said he soon became known as "the guy with the radar gun" because most high school coaches didn't use one, started coaching at Bryan in the '90s. In 1995, he had one of his pitchers do offseason work with a softball and a tennis ball to throw different weights, and continued from there.

Garman's return to the area in 2016 spread the idea further, including to Uhlenhake and then Gast and St. Henry. Garman learned the technique at Driveline, a company credited for revolutionizing private training for pitchers, amid an ultimately futile 26-month attempt to return from a shoulder injury that ended his minor league career.

The idea isn't new - former Dodgers pitcher Mike Marshall practiced it with six-pound iron balls in the 1970s - but social media and companies like Driveline have marketed it to a wider audience in recent years. The basic principle is that throwing a heavier ball, around 11 ounces to a pound or two, takes more effort and exposes flaws in a pitcher's arm path. Once he learns how to throw the ball in the most physically efficient way possible, a lighter ball helps him repeat throwing the same way but faster.

"I don't want to have to say anything," said Garman, who now runs camps during the offseason and helps train about 30 high school pitchers a year. "I want the ball to give him the feedback he needs. … I just want to ask good questions and get him to think, and then have him throw the ball and make the connection between the two, and figure out where he should go or what he should be doing to feel his best."

Gast implemented an offseason throwing program including overload-underload training in the fall of 2020, and the pull-down velocity - the speed at which the ball leaves the pitcher's hand, the measurement of which is also a relatively recent development - of players who were measured all of the last three years increased by an average of 9.78 mph from 2021.

Some went up 15 or 20 mph, which Gast attributed mostly to growth spurts, while others gained as little as 2 mph. Overall, though, Gast said that those who came to at least 75% of the sessions averaged about a 5 mph increase per year.

St. Henry's Dominic Schwartz throws a weighted ball during a practice.

Wells related how a college teammate, Luke Haggerty, took up weighted ball training about two years ago while training high schoolers, then had a pro tryout at 37 shortly after.

"When he was a supplemental first-round draft pick out of Ball State, he was throwing 94 miles an hour," Wells said. "At 37, from doing weighted ball training - because he trained guys and he won't let his students do anything he hasn't already done himself - he threw 98 that day."

Held also credits increases in velocity to more long toss, saying that throwing for distance forces a pitcher to "throw with intent" and give maximum effort, and Garman often uses weighted balls for long toss sessions with the Dragons.

Held pointed out that in basketball, playing in a game provides everyone plenty of reps. In a baseball game, pitchers can only throw so many pitches and fielders and hitters only get three or four chances or at-bats per game.

"For years, most guys would rather compete and hated the training part," Held said. "Guys just wanted to play, man, you know what I mean? Now, if you talk to college coaches, it's been a total reversal. Now kids like to train."

Garman said that any throwing program has three central components: frequency, intensity, and volume. If a pitcher adjusts his intensity and volume, he can throw every day.

"Intensity and volume, what are you trying to get out of today?" Garman said. "Is it a recovery day, is it a long toss, high-output day? Are we throwing a bullpen, throwing a game?"

"That was something that I probably messed up," he went on, "where, like, once I was loose, I was just firing BBs. And I look back on it, I'm like, 'Why did I do that?'"

Klenke said the Cavaliers have four pitchers who are at least touching 80 mph, but he hasn't pushed for more velocity. In part, he believes that command is more important, but mostly, it's because his primary focus is keeping his pitchers healthy.

"One thing that I pride myself on, and that Coach Harlamert would pride himself on, is, you know, maybe our guys don't throw necessarily the hardest velocity-wise, but we typically don't have arm injuries," Klenke said. "And a healthy arm is better than one that throws hard, but isn't healthy when you need it to be."

Gast and Klenke have both introduced resistance band workouts for pitchers, and Klenke said that working with the bands for five minutes before throwing and five minutes afterward was enough to see the benefits.

The recovery work helps counteract the force of throwing on the muscles, according to Coldwater trainer Tiffany Rutschilling.

"They have to do another set of bands afterwards to kind of pull the muscles down," she said. "It's a negative, so they'll do the movement and then return at a slower pace. They're kind of pulling the muscles in the opposite direction - you're going forward all this time, and now we're going to pull these muscles back."

Rutschilling said the Cavaliers often focus on strengthening and stretching the scapular muscles to keep strain off the biceps and triceps. By rotating properly and relying on the scapular muscles, a pitcher creates a larger contraction and spreads the force over a larger area.

"If you don't have strong scapular muscles, which slow the arm down, instead a lot of times the triceps will kick in, which can cause (ulnar collateral ligament) injuries," Rutschilling said.

A St. Henry pitcher works out with resistance bands, which multiple area teams use to help pitchers avoid arm injuries.

Uhlenhake, who did band work with Garman while in high school, noted a case of golfer's elbow when his forearm tightened up throwing a cutter at Indiana Tech, but said that deep-tissue massages and in-season strength training has helped him avoid injuries.

With weighted-ball training, Garman likes to point out that kids freely throw two-pound footballs without worrying about injury, so a one-pound weighted ball isn't out of the ordinary.

The greater risk comes from throwing the lighter balls, which can be done faster and puts more stress on tendons rather than muscles.

"That's something that I hesitate with, because Brian knows what to look for," Gast said. "So we try to really limit the underload throws for most of our guys, unless it's a more mature kid, a stronger guy that maybe we can do a little bit more with. But I'm real hesitant to push that too far without having Brian there to say, no, that's too much."

"When people blow up elbows and shoulders, it's the velocity with which the action happened," Garman said. "It's the tendon or ligament that meets its threshold and can no longer hold it. It's the velocity that the elbow extends to throw the fastball. General rule is, you can't throw heavy stuff as hard. Therefore, you can't create the velocity and stress on the joints with the heavier stuff."

Rutschilling is hesitant about weighted-ball throwing on account of open growth plates in teenager's elbows, shoulders and wrists, which she said make them more vulnerable to injuries than adults.

"It's yanking on those growth plates, which are already weak to begin with," she said. "If they're done properly, I'm sure they're safe. But just from experience, a number of times I've seen coaches say, 'OK, go do this,' and they don't really demonstrate exactly proper mechanics and that sort of thing. Yout have so many different areas that you're going to be stressing, and then you put a weight in their hand, and baseball players tend not to go 50%. They tend to go hard."

Garman noted that when he instructs his pitchers to lob a heavy ball softly against the wall, there are always a couple who fire it regardless and have to be corrected.

Bailey said that two or three out of every 10 pitchers he recruits come in with elbow or shoulder soreness, but that it stems from throwing breaking balls incorrectly rather than chasing velocity. From an injury standpoint, he said there were few downsides to throwing faster speeds.

"When they throw a fastball, it's a straightforward motion," Rutschilling agreed. "When we start doing the off-speed where we're turning the wrist or rotating the forearm, it's putting more pressure on those growth plates. Obviously you want to work your way up to (velocity)."

Rutschilling said that she'd only seen one or two season-ending baseball injuries in her 11 years at Coldwater. Held said that Defiance hasn't had any season-ending injuries since he started in 1999 and has rarely had a pitcher miss a start in the spring. Most of the injuries he's seen have come at offseason showcases, where guys try to throw hard without ramping up properly.

But he does think that there are more arm injuries in high school than there used to be.

"The harder you throw, the higher risk for injury," Held said. "But if you don't throw hard, you're not going anywhere. So it's a choice you have to make."

The main cause coaches cited for a smaller spike in velocity in the Grand Lake area was the prevalence of three-sport athletes.

Uhlenhake and fellow Redskins fireballer Nolan Schmitz only played baseball, although they also hit and played in the field when they didn't pitch. Wells said he hadn't had a full-time pitcher or full-time baseball player at New Bremen, and Klenke said that all Coldwater's top-end pitchers since he came back have been multi-sport athletes, usually football players.

"One of the biggest advantages is that they're not only physically strong, but mentally strong, because football is a grueling sport," Klenke said. "And they're team-oriented, they'll play together, familiar with one another and their expectations and things like that."

"But then one of the disadvantages is that fall is a time where you can really increase velocity, because the weather's still nice," he continued. "It's at the end of seasons when you can really help improve velocity … there's only so many hours in a day, and when the kids are playing basketball or playing football, they need to be focused on that, for sure."

Gast said his fall throwing program is optional and has no effect on who gets reps in the spring, in large part so that kids who want to spend that time focusing on football can do so.

Even at Defiance, a Division II school, most of Held's players are two- or three-sport athletes, which limits their ability to throw in the offseason.

"In our area, with our school size, we only have so many athletes, so we have to share them in order to be competitive in as many sports as possible," Wells said. "That's always how it's been. We can't get into the specialization of sports with single athletes, because that would be very much to the detriment of a lot of our programs."

Garman recalled training a high school senior who also played other sports and was only able to show up once a week, but found time to throw weighted balls in between. When Garman got him into a showcase in the winter, he had gone from 83 mph in the summer to reaching 91 mph with his first three pitches, and he was offered a Division I scholarship the next day.

But Garman added that even if a player is willing to throw year-round while playing another sport, it can raise the risk of overuse injuries.

"You've got to be willing to turn that off too and just be like, 'I'm smoked,'" he said. "'I had football or basketball practice, and now my legs are cooked, and I have to be willing to just lay on the couch or just go to bed before 10 o'clock. And if that means I don't throw today, then so what?'"

"There has to be a certain awareness," he said, "and a willingness (to stop) when you do notice you're tired. We don't want to be throwing fatigued."

Regardless of the spread of velocity training, local pitching hasn't shifted to all fastballs, all the time.

Uhlenhake went from throwing 77 mph as a freshman to 91 mph the summer before his senior year, and he estimated he threw a little over 60% fastballs and sliders the rest of the time. In college, he started prioritizing his changeup more and said he switched to about 55% fastballs, 30% sliders and 15% changeups.

"You definitely want an off-speed," Uhlenhake said. "You can't dominate games with just a fastball, but I think you can win with just a fastball. Your off-speed might not be as good, but it's harder to hit."

Uhlenhake was a strong hitter in high school, but his career at the plate ended in college against an array of ever-stronger breaking pitches. When it comes to velocity, he said it mostly makes a difference at the very top end.

"I'd say (going) 80 to 85, there's a difference, but I think it's much more drastic when you get from 85 to 90, 90 to 95," he said. "Just because then all speed starts being much harder, you can't see the spin as well. It just mixes together."

Former St. Henry pitcher Ryan Uhlenhake, now a sophomore at Indiana Tech, seen pitching in his senior year in 2021.

Rather than fastballs taking over, Held said changeups have been more on the rise in the last 20 years. In his current throwing workouts, he has his pitchers alternate throwing fastballs and changeups, where 20 years ago most teams, including Defiance, relied on fastballs and curveballs.

"The changeup's always been around, but if you had a guy who threw 90 with a hammer, you weren't throwing a changeup, that'd be stupid," Held said. "But that's changed. We train so much more with the changeup, and the changeup's actually a better pitch, because you can command it better, you can locate it better, you throw more strikes with it. With a big breaker, it's harder."

Bailey said that pitchers learning to throw changeups earlier had led to better command as well, and observed that placement of breaking pitches has gotten better, which he attributed to good coaches teaching kids to throw off-speed properly and maintain their arms.

Like Klenke, Wells' coaching philosophy revolves around control rather than velocity, and he pointed out that New Bremen's field tends to get strong winds in from centerfield, incentivizing pitching in the zone to win games. He said several Cardinals pitchers had success by "pitching backwards," throwing breaking balls in traditional fastball counts and vice versa.

"That doesn't show up on the radar gun, but it's perceptual speed," he said. "That's where the pitch ability comes in and that kind of stuff, where you appear to be throwing faster than what you actually are."

Held has coached four major pitchers, and he said that throwing hard has always been the key to getting drafted, going back to his playing days. But other areas have caught up to him in velocity training.

"To get drafted, our whole thing was, you have to get to 90 or you have no chance," Held said. "Now, the 90 is 95. If you don't get to 95, you don't have a chance."

At smaller programs, velocity is still key to getting outs, but the bar isn't quite so high.

"For us at a competitive college level, we want to see somebody that's throwing mid-80s, mid to upper-80s, with the potential to get into the 90s," Bailey said. "But you also need the kids that are in between there, so when you do have the ones that throw hard, then you can bring in a kid who's throwing 80 to 82 with breaking stuff in the 60s to low 70s. It makes a big difference, kind of complements the kid that throws harder."

Garman said that he doesn't want kids to chase scholarships, at least not primarily. He aspires more to help them maximize their potential and become All-Ohio pitchers. But if their goal is to get to Division I, he'll help them put in the work to get there.

"In order for you to create an opportunity for yourself to go to college, you have to be more serious about it now than you've ever had," Garman said. "And I don't know how much I even like that. High school sports should be fun, shouldn't be about working towards their scholarship."

Held said the aftermath of COVID-19 and changes in the NCAA have made it harder to get offers at the higher levels of college baseball as well. Gast said that when Uhlenhake signed with Indiana Tech in December 2020, he had trouble getting schools to take notice of his star pitcher despite the fact that Uhlenhake was hitting 90 mph before his senior year.

Nolan Schmitz followed Uhlenhake and joined the Warriors. But Gast's ace this year, junior Devin Delzeith, has a different skill set, relying on strong command and posting sterling stats while working around 81 to 83 mph and topping out at 85 mph.

"I hope like heck we can find a landing spot for Devin, because I think Devin is as good of a pitcher as we've had here in a while," Gast said. "He's not touching 92, but I think his stuff is really good."

Building muscle mass and particular training can raise a pitcher's limits, but not erase them. At a certain point, kids will max out. But figuring out where that point lies is murky.

"Some kids are going to max out at 75 miles an hour and that's all," Gast said. "At least, maybe. Maybe that's my limitations, I can't get them to go farther because there's something that I can't see."

Garman puts the number higher, asserting that every male high school athlete could hit 80 mph with proper strength, nutrition and throwing work.

Held agrees.

"Absolutely, no doubt," Held said. "I mean, if you've got any ability. You can't take some guy off the street who can't walk and chew gum. But yes, and I believe on top of this - and I've been saying this for years - I believe there is a 90-mile-an-hour arm in not only every school in the country, but there's a 90-mile-an-hour arm in every class, every grade in every school of the country. And a lot of them don't play baseball."

Gast says that his throwing program can be replicated by anybody, that any team could see average jumps of 5 mph per year, provided the kids buy in.

But even with more and more kids throwing in the 80s, or even 90 mph, it hasn't completely changed high school pitching.

"We still face a lot of guys that throw 75 to 80 miles per hour and are very effective," Held said. "Lefties that throw 73, they get us out all day long and all night long. You don't have to throw hard to get people out, that's for sure."