Only the road between New Bremen and Minster bears the name Amsterdam now but 175 years ago a town with the same name sat on the banks of the canal.

NEW BREMEN - The only reminder of a small, bustling 1880s canal town is a road named after it.

Local historians hope to remedy that by putting up a commemorative marker.

Amsterdam, originally located between Minster and New Bremen, existed for just a few years from 1837-1849. All of its residents fell victim to cholera.

"No man, woman, or child escaped the ravages of the awful disease," states an article in The Towpath, a quarterly newsletter of the New Bremen Historic Association (NBHA). "There was no human being left to carry on. Their habitation decayed, returned to dust, and Amsterdam became a rapidly vanishing memory."

The Towpath editor Genevieve Conradi and others are on a mission to bring awareness to the long forgotten settlement.

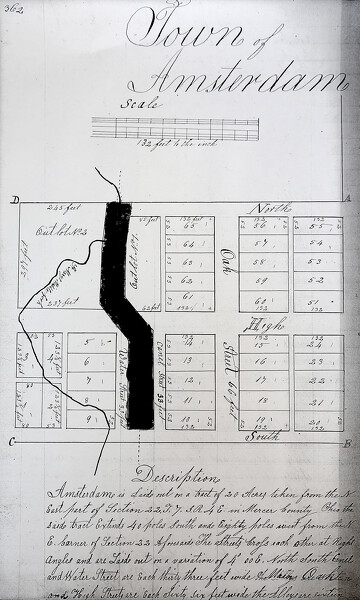

A plat map shows the layout of Amsterdam of 1849.

From the New Bremen Histoical Society

German immigrants in 1837 platted the 65-lot town of Amsterdam along the Miami and Erie Canal, according to The Towpath. It had about 20 houses, several stores, factories, a grist mill and a distillery.

"I don't think it's well known," Conradi said. "I don't like the name 'ghost town.' (Amsterdam) was a town that was there but (just) disappeared."

NBHA members Dennis and Gen Dicke late last year said the organization has an opportunity to commemorate the abandoned town through the William G. Pomeroy Foundation's Hometown Heritage Marker Grant Program.

It has applied for the sign and is waiting to hear back.

The Asiatic cholera epidemic arrived in what is now known as Auglaize County in June 1849, according to The Towpath. It would go on to decimate populations in New Bremen, Minster and Amsterdam.

All that's left of the little town of Amsterdam is a road sign.

Cholera, an acute diarrheal illness caused by intestinal infection, was prevalent in the United States in the 1800s but water-related spread has been eliminated by modern water and sewage treatment systems, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The infection is often mild, but can be severe and even fatal if left untreated. Severe symptoms include watery diarrhea, vomiting, leg cramps, dehydration and shock.

A person can get cholera by ingesting contaminated water or food, per the CDC. In an epidemic, the source of the contamination is usually the feces of an infected person.

The deaths were so often that "bodies, in crude coffins, were gathered twice each day and taken to the cemetery for burial without benefit of mourning or religious ceremonies," the newsletter reads. "A simple sign, such as a piece of white cloth hung on the front door, indicated the presence of another victim or victims. The deceased were buried four tiers deep in two trenches, each seven feet wide."

The residents were interred in a mass grave across from St. Paul's Church on North Herman Street in New Bremen. A public park was built over the graveyard in 1948 and the remaining headstones were laid flat and buried. Amsterdam's former plat was annexed into New Bremen in 1876.

"When the big cholera epidemic took many, many lives in 1849, they (residents) decided they did not want the cemetery in town," the newsletter reads. "That's when they went to Lock Two and built the new cemetery. (The bodies) are probably buried in the St. Paul cemetery because that was the one being used at that time. They (church officials) offered to move any (bodies)…but I don't think anybody wanted that so what tombstones were there, they just laid them flat and covered them over."

A photo of New Bremen taken in the late 1800s gives a glimpse of what Amsterdam may have looked like. Hitching posts and muddy streets.

From the New Bremen Histoical Society