Sam Fledderjohann was part of a record-breaking synchronized chain of 20 kidney transplant surgeries that saved the lives of 10 people.

CELINA - Motivated by the desire to potentially save a stranger's life, an Auglaize County woman last month was a part of a record-breaking synchronized chain of 20 kidney transplant surgeries that saved the lives of 10 people.

Sam Fledderjohann, of New Bremen, didn't know anyone specifically in need of a kidney transplant when she first reached out to the Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center in February 2024.

"I thought, 'Wow, I wonder if I could be of help to one of these people,'" she said. "I sent an email out to Wexner … And then, honestly, I didn't really expect to hear back from Wexner so quickly. Within 24 hours, they had sent me a video and they said, 'Do you have somebody specific?' I said, 'I don't,' but let's just start the process and see. And, then they send you a video (with information) and (are) very, very transparent."

A kidney transplant is a surgery that places a healthy kidney from a living or deceased donor into a person whose kidneys no longer function properly, according to the Mayo Clinic website.

The kidneys are two bean-shaped organs located on each side of the spine just below the rib cage. Each is about the size of a fist. Their main function is to filter and remove waste, minerals and fluid from the blood by producing urine.

"When kidneys lose this filtering ability, harmful levels of fluid and waste accumulate in the body, which can raise blood pressure and result in kidney failure (end-stage renal disease)," the website reads. "End-stage renal disease occurs when the kidneys have lost about 90% of their ability to function normally."

After Fledderjohann reached out to Ohio State, things moved quickly. Fledderjohann, who is also the Special Olympics coordinator at Mercer County Board of Developmental Disabilities, got all of the required testing done and reached out to friends on social media to see if there was anyone locally in need of a kidney.

"It turned out I wasn't a match for any of them," she said. "So I really still felt the need to (donate). I just really felt like I was supposed to do this. So I went in as a non-directed donor, and I just told them at Wexner, I said, 'I'm here if you need me.'"

A non-directed donor is someone who donates an organ to a stranger with no knowledge of the recipient's identity or characteristics.

Fledderjohann just had one stipulation for the specialists at Wexner: If the procedure is scheduled, make it after the harvest season, as her husband is a farmer.

Following harvest, she received word from Ohio State that they were planning something special with her in mind, she said.

"Well, that time period kind of came and I didn't hear from them," she said. "And so I messaged them and they called back and they said, 'Your ears must be burning. We're working on something that we think is going to be life-changing for a lot of people, but we're missing one thing. We're just crossing our fingers. All the stars have to align. We need you to go take this DNA test.' So I went to Lima and I took the DNA test, and lo and behold all the stars aligned and I was the match for the first person."

Fledderjohann's surgery, which took place on Dec. 13, was one in a synchronized chain of 20 surgeries that set a Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center Comprehensive Transplant Center transplant record and transformed the lives of 10 people, according to an Ohio State news release.

The single-institution living-kidney-donor transplant chain took place over two days. Five donor and five recipient surgeries were performed on each day. Surgeons transplanted healthy kidneys from 10 different donors into 10 recipients who otherwise could have waited years for a transplant.

"This is one of the country's largest single institution living kidney donor transplant chains completed in one week," Kenneth Washburn, M.D., executive director of the Comprehensive Transplant Center and director of the Division of Transplantation Surgery at The Ohio State University College of Medicine, said in the news release. "Big chains like this one allow us to help a large number of patients in a short period of time. The resources needed to complete an event such as this is a testament to the commitment of the Ohio State Wexner Medical Center to enhancing and extending patients' lives through organ transplantation."

Paired kidney donation happens when a person in need of a kidney has a living donor that's not a compatible blood or tissue match, the release explains. The transplant team then links incompatible donor/recipient pairs with other incompatible donor/recipient pairs to form a chain, so each recipient receives a compatible organ. The transplant swap begins with an altruistic non-directed donor. The final recipient is a person on the transplant waitlist.

In this case, Fledderjohann was the altruistic non-directed donor.

The transplant team began planning for the chain in October. Once the living donors and recipients were identified, the coordinators worked closely with the patients to keep the chain intact. A change in health status as simple as a cold or fever could have broken the exchange.

Sam Fledderjohann, right, with the recipient of her kidney donation, Scott Humes.

Fledderjohann was even able to meet her kidney recipient, Scott Humes.

"My sister made a very good point when I was telling her about when I got to meet him," Fledderjohann said. "She's like, 'You know how few people in the world have ever experienced that?' And I thought, that's so true. You know, (he was) just a stranger. And just to be able to say, you know, now part of me is (in him). Getting to meet him … I would never have asked (for) that, but that he asked to (meet me). It was pretty special. Just such a good young (person), he's in his 20s. And yeah, now he has a full life ahead of him."

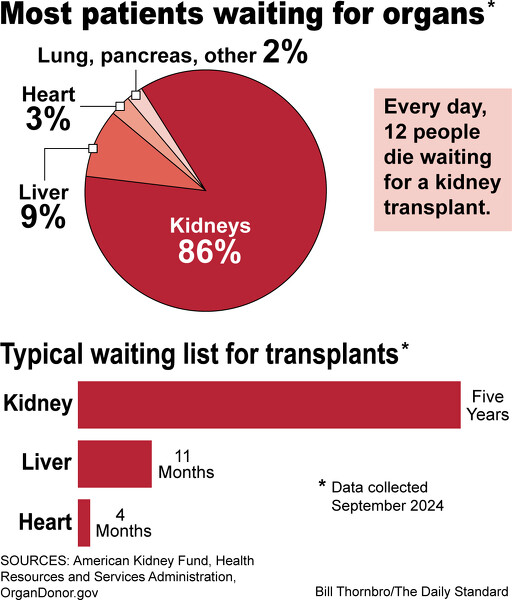

Organ transplant needs.

According to the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network, there are 104,840 people on the transplant waitlist and 90,506 of them need a kidney. Of those 90,506, 2,079 live in Ohio.

The 10-way transplant chain that Fledderjohann was a part of is believed to be one of the largest single-institution chains in the nation, according to the Ohio State news release.

For more information on becoming a living kidney donor, go to www.wexnermedical.osu.edu/transplant/living-kidney-donation.

Another way to help save someone's life is to donate blood. There are multiple, ongoing ways to do so locally.

Mercer Health utilizes nearly 700 units of blood on an annual basis for patients requiring transfusions to replace blood loss from surgical procedures, accidents or treatments for certain diagnoses.

Their next blood drive is Jan. 21. For more information or to make an appointment to donate, go to www.mercer-health.com/donate-blood/.

The American Red Cross will hold multiple blood drives in the Grand Lake Region in January 2025.

St. John Lutheran Church, 1100 N. Main St., Celina, will host a drive from 12 to 6 p.m. Monday.

Celina American Legion Auxiliary Unit 210, 2510 State Route 703, Celina, will host a drive from 1 to 6 p.m. Jan. 9.

Parkway High School, 400 Buckeye St., Rockford, will host a drive from 8 a.m. to 2 p.m. Jan. 15.

Celina Insurance Group, 1 Insurance Square, Celina, will host a drive from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m. Jan. 17.

The Fraternal Order of Eagles 3025, 101 W. Walnut St., Coldwater, will host a drive from 12 to 5:30 p.m. Jan. 17.

American Legion, 601 N. Second St., Coldwater, will host a drive from 12 to 6 p.m. Jan. 20.

Rockford United Methodist Church, 202 S. Franklin St., Rockford, will host a drive from 12 to 5 p.m. Jan. 31.

For more information or to register for an American Red Cross blood drive, go to www.redcross.org/give-blood.