CELINA - Though dinosaurs are the most notable of the prehistoric animals, smaller mammals and fish walked and swam in Ohio, some species even buried underneath your feet right now (and all still larger than what humans would be comfortable with).

Millions of years before the ice age, Ohio was covered with water, as evidenced by the remains of prehistoric sharks in eastern and southeastern Ohio. More recently - thousands of years ago - massive mammals, including elk, walked in what is now Mercer County.

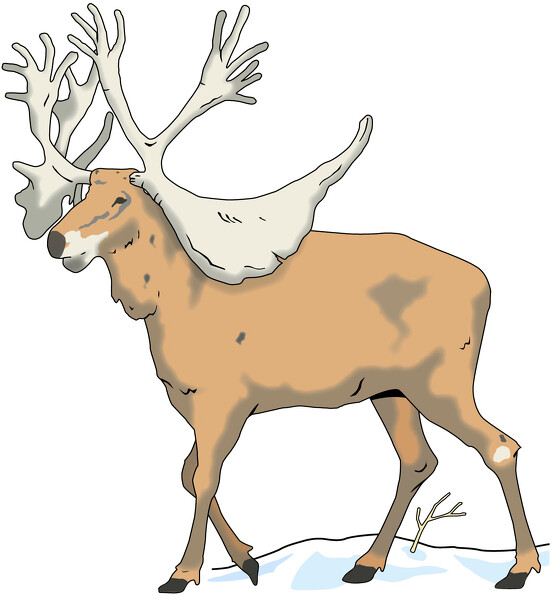

These antlers were discovered on a Mercer County farm in 1981.

The antlers of a prehistoric elk are on display inside the Mercer County Historical Museum in Celina, showcasing Ohio's rich history in fossils.

In the early 1980s, officials excavated a nearly complete elk skeleton in a peat and marl deposit in Cranberry Prairie, historical society director Cait Clark said.

"They realized it was a pretty significant find right away," she said. "You pull these huge antlers out of the ground, that's not a normal deer."

In November 1981, Ron Schwieterman of Cranberry Prairie unearthed part of an elk skull and a large antler rack on the Ron Stucke farm, while excavating for a drainage ditch near Vandenbush Run, southwest of Cranberry Prairie, according to information from the Ohio Journal of Science. Schwieterman dug about 1 meter below the surface. On May 4, 1982, officials with Ohio State University and the Ohio Historical Society and other local personnel assisted in the excavation.

When the animal was carbon-dated between 1981 and 1985, it was estimated to be 9,370 years old, making it about 9,410 years old in 2025.

"This elk was recovered in a pretty decent condition," Clark said. "There were a few bones missing, but one of the most interesting things that they discovered was it had a wound in its shoulder blade. It is looking more like an injury dealt from an archaic Native American point. A paleo-Indian or early archaic human would have injured this elk mortally by the looks of it because it didn't show any signs of healing. It is the only injury noticed on the bones which, if this was a rut-related injury, there would have been more. There would have been more evidence of a fight."

Because the wound was intact and there was no other evidence of a fight, officials believe hunters shot the animal with a spear.

"Another thing they theorized happened to this elk was that there used to be a prehistoric lake over by Cranberry Prairie," Clark said. "If it was killed by archaic people, it would have been harvested. The skeleton would have been scattered, there would have been evidence of it being cooked and rinded for a meal, but there wasn't anything like that on this elk. They think that it was mortally injured by a paleo-Native American point (spear or arrow), but they believe that perhaps it survived long enough to flee into the bog where it got stuck and then it couldn't be harvested. It would have died in the bog and the natives from this area wouldn't have been able to access it."

Clark said the large portion of the skeleton being intact solidifies the theory the animal died without being harvested. She also said the wound is evidence that people hunted and were here in Ohio.

"The whole find tells a story, and that's rare," she said.

"At the time when it was discovered, it was one of the most complete skeletons," she said. "It's very rare to find well-conditioned skeletons (in this area) because if you think about it, most of this is farmland and nobody's digging deep. The plow zone is 6 inches. Nobody's really delving down in, and when they are, maybe they'll find something, but something prehistoric, an animal like this, you don't usually run across it very frequently on this scale."

Cervalces scotti

Also called the stag-moose, this animal was about the size of a modern moose and had huge antlers.

Clark said throughout the ice age there were periods of colder and slightly warmer shifts, as there were throughout the much longer Pleistocene - a geologic epoch that ranged from 1.8 million to 10,000 years ago. Despite animals' ability to handle the weather shifts for thousands of years, at the end of the Pleistocene, there were mass extinctions.

"The Pleistocene came to an end rather suddenly and that's when we saw some some serious changes in this area in particular," she said. "There used to be coniferous forest like none other that exist today. It starts to warm up at the end of the Pleistocene era and there's this sudden spike in the cold again, and it's during this spike in the cold that we start seeing some serious mass extinctions. It started to bring about the disappearance of our large mammals that were in this area."

Clark said officials aren't sure of the cause of the mass extinctions, but some theories include human involvement.

"According to a controversial theory, first proposed in the 1960s, human hunting around the close of the Pleistocene caused or contributed to the extinction of many of the Pleistocene large mammals," according to information from the University of California Berkley's Museum of Paleontology. "It is true that the extinction of large animals on different continents appears to correlate with the arrival of humans, but questions remain as to whether early human hunters were sufficiently numerous and technologically advanced to wipe out whole species. It has also been hypothesized that some disease wiped out species after species in the Pleistocene. The issue remains unsolved; perhaps the real cause of the Pleistocene extinction was a combination of these factors."

Some of the animals that lived here include sabre-toothed cats, American elephants, mammoths, giant sloths that stood about 12 feet tall, giant beavers that came up to an adult man's hip, short-faced bears, giant armadillos and dire wolves. They started to disappear about 14,000-12,800 years ago.

"The thing was that these animals had experienced that Pleistocene era where the temperature was fluctuating every thousand or more years, but the species were surviving so why did they suddenly die?" Clark asked. "One of those reasons is that humans were beginning to evolve into more efficient hunters. They were learning, too. You had humanity coming in and essentially wiping (the animals) out very suddenly. I'd say the Younger Dryas (another geologic epoch) and human hunting are what really started to kill off those large mammals."

Clark said the changing climate played a part in the exodus.

"You have to remember at that time, this land was changing very quickly," Clark said. "About 12,000 years ago, this was all coniferous (forest) - deciduous trees were starting to move north, and that could have been a factor for the elk as well - why it would have died out. It didn't have the same food source."

She said the deciduous trees, including beech, hickory and maple, moved north and the animals followed their food source.

"The wildlife that we have reflects what we humans have done to the land," she said. "We don't have space for wolves. If we created space for wolves, there would be wolves. As humans have cultivated and tamed the land, we've lost a lot of that native wildlife. Like we used to have buffalo here. We don't have the space for it anymore. We created farmland and subdivisions. I would say (humans) played a heavy role."

Cladoselache

This strange eel-shaped creature was one of the first sharks. Scientists say it was probably quick in the water and agile thanks to its long, streamlined torso.

It appeared at a time when much of this area was a shallow ocean. Many well-preserved fossils have been found around Lake Erie.

Cladoselache went extinct about 300 million years ago.

Although not necessarily in Mercer and Auglaize counties, ancient sharks have been found in eastern and southeastern Ohio.

Dan Cline, an environmental science Ph.D. student at Wright State University-Lake Campus, discussed the sharks and other fossils as part of a presentation for his thesis.

Cline said throughout his research, he is often in awe "that we're seeing some of these things for the first time in millions of years."

Some of the sharks Cline discussed include the Cladoselache, or an 8-10-foot long shark that lived during the Devonian period, known as the "Age of Fishes," about 300 million years ago when a shallow sea covered the area.

Although not a shark, the Dunkleosteus terrelli, nicknamed "the Dunk," was a fossil fish that is comparable to a Great White, Cline said.

"The Dunk was the top predator near the end of the Devonian period, and it belonged to a now-extinct group of fish called placoderms, or 'plate skin' fish," according to the Ohio Department of Natural Resources.

"Like other placoderms, a portion of the Dunk's body was covered with bony plates, like a layer of armor," ODNR's website reads. "The Dunk cruised the surface of a sea that once covered Ohio. It had a strong, fast bite and might have eaten early sharks, bony fish, smaller placoderms and ammonoids (animals related to squids that had coiled shells)."

Cline said the Dunk ranged from 15 to 20 feet long and ate smaller sharks, like the Cladoselache.

A fish's diet depended on the species and whether its teeth were more stab-like or crushing.

Cline said there was no definitive reason the sharks and fish died out other than natural selection.

There are no dinosaurs found in Ohio because either the younger sediments and fossils from the Mesozoic and most of the Cenozoic eras were never deposited in Ohio, or they eroded away before the present day. Despite this, the state has a rich fossil record spanning more than 150 million years.

For example, the bedrock in Mercer County is part of the Silurian period, or rocks that are 443-419 millions years old.

Cline, who is in the third year of his doctoral program, says he now understands that prehistoric animals and fossils are much more than just dinosaurs.

"Growing up, thinking that Ohio was kind of barren in terms of fossils, this has shown me that there is really a rich fossil history that is unfortunately overshadowed by the dinosaurs … even the ice age fauna," he said. "The big takeaway was that there was a great diversity of prehistoric creatures here, and I'm hoping to just share it with people and hope other people can get excited about it."