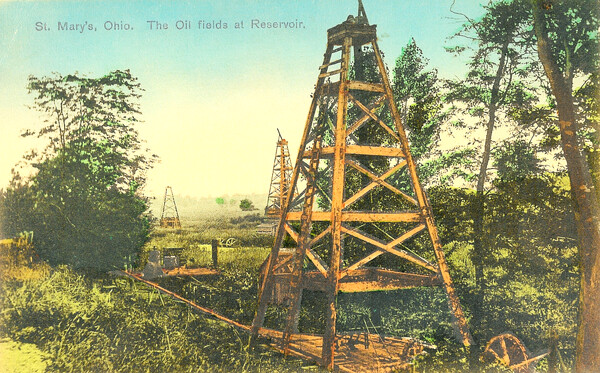

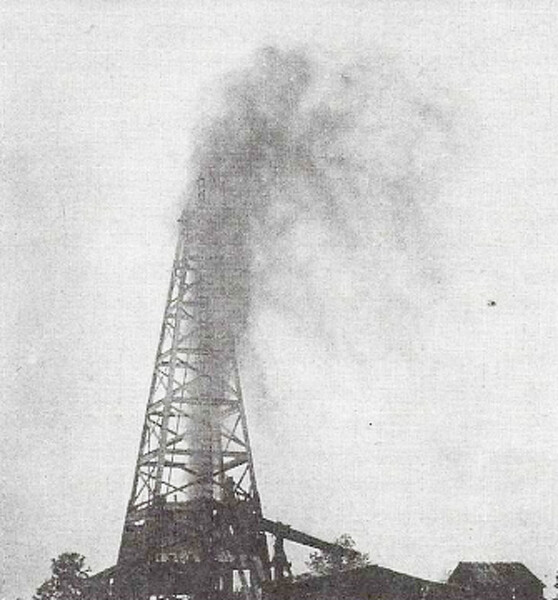

This postcard shows some of the oil derricks that used to surround Grand Lake.

CELINA - In addition to once being known as the largest man-made lake on the planet, Grand Lake introduced to the world freshwater offshore drilling, laying the groundwork for the modern petroleum industry and igniting a local economic boom that reverberated for decades to come.

"In the 1890s, Grand Lake St. Marys actually became the site of the first freshwater offshore oil wells," Mercer County Historical Society Director Cait Clark told a large crowd at Lake Improvement Association's meeting on Saturday. "In 1915, the lake was home to more than 150 oil wells, and it really set the stage for all of those inventions and creations that were going to take place as a result of the first steps toward offshore freshwater drilling."

This was all made possible by the discovery of a subterranean natural gas formation near Findlay in 1884, according to Clark. Dubbed the Lima-Indiana trend, the formation spanned 260 miles from north-central Ohio to east-central Indiana.

"They realized it was going to be a very valuable resource if they could use it. So the people who discovered it, they started tracking it all the way into Indiana," Clark said.

It also was found to extend southward to the Grand Lake region.

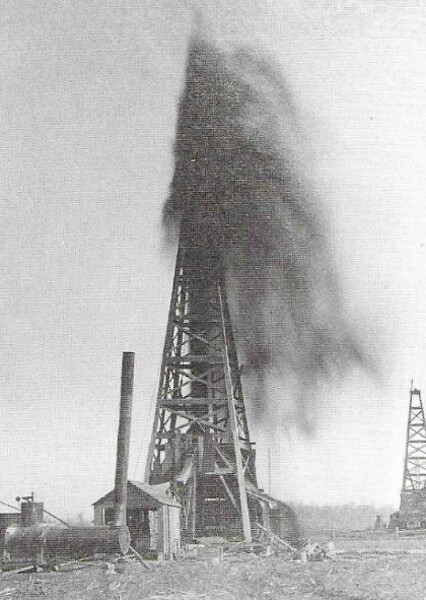

A Grand Lake area oil derrick blows its stack, provided by Mercer County Historical Society Director Cait Clark.

"In June of 1886, the first well was dug here in Celina, and one month later … the first well was dug in St. Marys on the east side, and locals actually began drilling wells in their backyards on the beach," Clark said. "It was these very early private-property type wells that actually made history."

The wells attracted national attention and investment. Among the earliest oil entrepreneurs, however, was none other than the Riley family, whose patriarch James Riley platted Celina in 1834.

"People realized, 'Oh, perhaps this is something that can be done not just on the shoreline, but maybe we could move out into the water as well,'" Clark said of the genesis of the first offshore drilling operations.

The Riley Oil Company commanded the Riley-Mosher well that began producing in 1886, Clark pointed out.

"It was actually active until the year 1910, and it was this well in particular that really caught the attention of outside investors that started to come into this area," she said. "Two of those companies were the Neely Clover Oil Company and the Manhattan Oil Company."

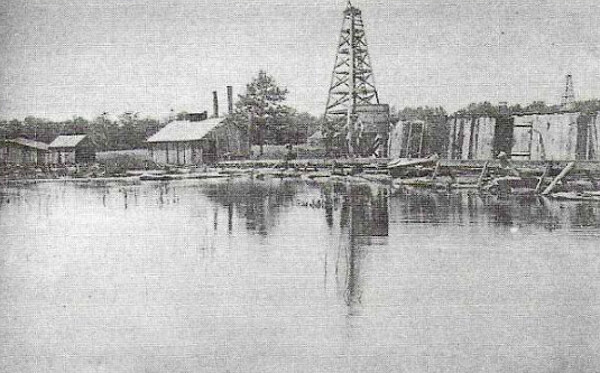

Wells were developed throughout Grand Lake and oil extracted by a number of means, including derricks supported by wooden cribs.

Auglaize County played a big part in the Lima oil fields in the late 1800s. Hundreds of oil derricks dotted Grand Lake after the first offshore derrick was built in 1891.

"These oil drilling machines were everywhere," Clarke said. "These were essentially early offshore drilling platforms. 'Cribs' were these large square wooden structures that were built on the lakebed, and they were filled with logs, stones, other debris to provide stability in the water. And then the derricks would actually be constructed on top of these cribs."

The system allowed for wells to be drilled directly into the lake, rather than just on the shoreline, Clark explained.

"This method was actually one of the first offshore drilling enterprises in the United States and actually predated all major offshore drilling that eventually took place in the Gulf of Mexico," she said. "It was a very significant step forward in offshore drilling."

Clark said there were instances of hand dug and cable tool drilling, also known as the sputtering method. A heavy tool would be lifted and dropped repeatedly to chisel away at the bedrock.

"This was actually a rather successful method used here at Grand Lake St. Marys because of the shallowness of the water," she said.

Steam-powered drill rigs and floating drill rigs were also put to use, but not to the extent of other methods.

"They were more of an experiment," she said. "These floating drill rigs were the precursor to offshore drilling platforms, and they were mounted on these barges or pontoon-like structures which allowed them to be moved to different areas throughout the lake."

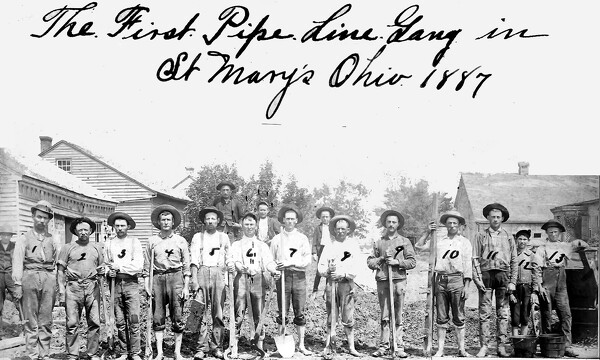

Auglaize County played a big part in the Lima oil fields in the late 1800s. There were many jobs on the pipeline, which were worked by crews like the one above, titled "The First Pipe Line Gang in St. Marys Ohio, 1887. Numbered individuals are: 1 John Boysell, 2 J. Helmstetter, 3 Ed Bates, 4 Thomas Mack, 5 Wesley Botkins, 6 William Swartz, 7 Tom Whitehead, 8 Charles Bubp, 9 Samuel Slife, 10 Frank Bulp, 11 Chas Upperman. 12 Wilbur Hunter, 13 William Wirwille.

Of course, it goes without saying that oil drilling can be a perilous undertaking, to both those who perform the work and the adjacent environment that suffers collateral damage.

"Oil drilling even today is a very, very dangerous endeavor. So we have multiple stories of deaths involving these companies and the people who worked for them on the lake, just tragedies," Clark said, drawing attendees attention to "Oil & Gas Boom, Mercer County and Midwest Ohio," a book containing first-hand accounts from contemporaneous newspapers.

It was authored by former historical society president Joyce Alig, who died in January 2024.

Early industry leaders, Clark said, also were aware of the threat oil drilling posed to the lake environment and made attempts to contain spills.

"There were a lot of environmental risks that were considered, even back in the early days of oil drilling here on the lake," Clark said. "They recognize that drilling in fresh water, especially in the area of such an agricultural community as this, it presented serious dangers. So they actually created wooden barriers and cribs that were used to contain the oil, just immediately around the platform."

Floating booms and oil skimmers were effectively used to contain smaller spills.

"These floating booms would track the oil into one specific area," Clark said. "Oil that was on the surface of the water, you would corral it with a floating boom, and then you'd use the oil skimmer inside of that boom to pull the oil off the surface of the water."

A picture of a St. Marys oil derrick provided by Mercer County Historical Society Director Cait Clark.

Tycoons and investors weren't the only ones to reap the benefits of the oil boom.

"It brought even more people in," Clark said. "You have to house these people. They're going to need medical services. They're going to need food. So all the locals that weren't directly involved with the oil drilling, they … became involved. They provided housing. They were providing all of these things that were needed for an influx of people coming in from everywhere in the United States to take part in this."

However, the oil rush ended up being relatively short-lived, with its mantle as an economic driver later taken up by manufacturing, agriculture, and tourism and recreation.

A combination of resource depletion and technological advancements enabling oil extraction in other parts of the U.S. spelled the end of the Grand Lake petroleum craze.

"If you are drilling in one space for a significant amount of time, you will eventually run out," Clark said. "That is what started to happen here. It really declined production, and production started to move to other areas of the country."

Advancements in drilling technology opened up productive oil fields in eastern Ohio, Texas and Oklahoma.

"These advancements meant that they could go further, faster, deeper, so they didn't have to just stay with these rudimentary methods of drilling that began here in Grand Lake St. Marys," Clark said. "There were also severe environmental concerns that were starting to take place, something that is still prevalent today. We know that there's a poorer water quality in the aquifer here on this side of the lake, and it's known that that is connected to oil drilling back then."

Furthermore, by the mid-1900s, other industries began expanding their footprint in the county.

"Agriculture really started to take up more of the space here in this area of Mercer County, specifically livestock, grain and dairy," Clark said. "We also had a lot of manufacturing starting to move in which brought even more economic growth in this area."

The area's status as a tourism and recreation destination blossomed as well.

"They started to remove the oil derricks," Clark said. "People started to come back to enjoy the lake in its more natural state. So there was fishing returning, hunting returning, boating was coming back, and it was becoming more popular again."

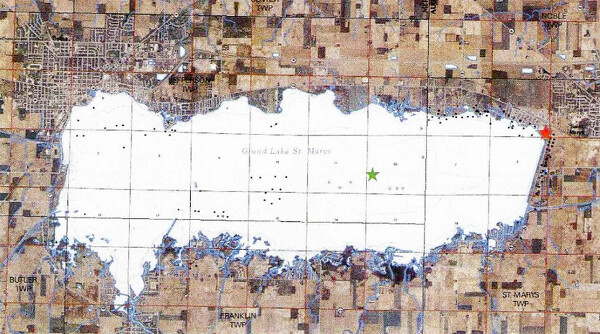

A map of Grand Lake showing locations of oil wells in and around the Lake, provided by Mercer County Historical Society Director Cait Clark. The red star is a historical marker. The green star is the approximate location of the "rock pile oil well site."

Even though the oil juggernaut strode on to more lucrative corners of the country, its presence is still felt today.

"There is a very strong legacy as a result of the oil industry in this area, so it actually had a lot of innovation regarding engineering and how oil drills would come to work later on in the modern sense," Clark said. "Offshore oil drilling in Grand Lake St. Marys was rather a pioneering type experience for that industry, and it helped advance oil extraction techniques and it actually influenced drilling practices in other parts of not just the United States, but also the world. There was an increased attention to the environmental awareness, too, and water pollution and conservation."

The vestiges of the oil boom are marked by signage throughout the Grand Lake region.

Also, the Grand Lake Recreation Club, Lake Improvement Association, the state park and various companies partnered in 2014 to haul 280 tons of rip rap to a site west of Anderson Road near the Mercer County Sportsmen's Club to install a replica oil derrick on top of an older one that has deteriorated.

The 4-feet-by-10-feet replica weighs 180 pounds and stands as a tribute to the hundreds of oil- and natural gas-producing structures that were once visible in and along the lake.

A picture of a Grand Lake area oil derrick provided by Mercer County Historical Society Director Cait Clark.