Friday, October 25th, 2013

Celina reports no problem with toxins in water supply

By William Kincaid

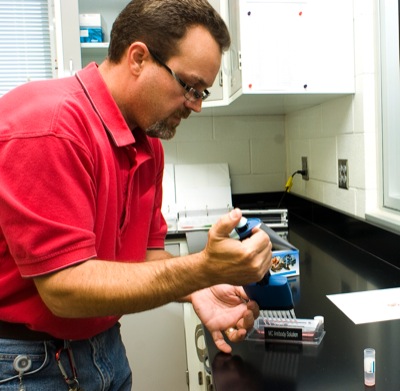

Photo by Mark Pummell/The Daily Standard

Celina water treatment plant assistant superintendent Todd Hone tests for toxins in the lab on Thursday morning. Microcystin toxins have never been detected in the city's drinking water, according to city officials.

CELINA - Some Ohio cities are spending more money to eliminate contaminants from their municipal drinking water, but Celina, which draws its water from Grand Lake, is continuing with the same successful treatment process it has used for years.

Microcystin toxins have never been detected in the city's drinking water, said Mike Sudman, Celina's water treatment plant superintendent.

"The plant is operated virtually the same way it was when I hired-in in '97," Sudman said. "We tweaked a few things here, changed the way we feed a chemical, but the general process hasn't changed other than now we run it through carbon and chlorinate."

City council members recently referenced an Associated Press story stating toxins from blobs of algae in western Lake Erie are infiltrating water treatment plants along the shoreline, forcing cities to spend more to make sure drinking water is safe.

One township even told its residents not to drink or use the water coming through their taps, the story said.

"We're not the only community that's (dealing) with this issue," councilman June Scott said at a recent meeting. "There are forces beyond our control."

"We have the facilities to treat it," councilman Mike Sovinski replied.

City safety service director Tom Hitchcock agreed.

"We don't have the microcystin toxin in our finished water like (other) communities do," he said.

Celina Mayor Jeff Hazel said chemical costs to treat the water have remained steady, with the city paying $570,000 in 2010, $545,000 in 2011, $580,000 in 2012, and, likely $560,000 this year and $580,000 in 2014.

This is the fifth consecutive year the state has placed a water advisory on Grand Lake due to unsafe levels of toxins produced by blue-green algae, also known as cyanobacteria. The advisory is posted when microcystin toxins exceed 6 parts per billion. The elderly, very young and people with compromised immune systems are told not to swim or wade in the water.

Between 2011 and 2013, average toxin levels in Grand Lake ranged from a low of 11 ppb in May 2011 to a high of 90.3 ppb in May 2013. The only months the average monthly toxin level dropped were in July 2012 and July 2013, when it went from 36.2 ppb to 29.1 ppb.

Regardless of the toxin levels in the lake, the city's final product contains no detectible amounts of microcystin, Sudman said.

"The majority comes out with clarification," he said. "Our clarifiers remove the majority of it just with potassium permanganate followed by alum polymer - that's where most of it comes out because you're removing solids and your algae in that process."

Alum causes phosphorous to coalesce and drop to the bottom before it is collected.

"After we go through clarification, we hit (the water) with ozone, a little more toxin comes out," Sudman said. "We lime-soften, and that's usually the end of the toxin."

Tests on drinking water in Carroll Township, just west of Toledo, showed the amount of toxins had increased so much in early September that officials decided to order residents to stop using the water for two days until they could hook up to another water supply. It was believed to be the first time a city has banned residents from using the water because of toxins from algae in the lake.

Toledo officials anticipated spending $3 million this year to treat its water, but the cost increased to $4 million because it has needed more chemicals to treat the toxins. The amount is about double what the city spent just a few years ago.

Sudman has thoughts on the reason why other treatment plants in the states are having difficulty removing toxins but said he doesn't know the other facilities well enough to speculate.

He said treatment operators from across the state often call him to discuss the issue. A lot of it, though, deals with tweaking the treatment process to maintain the right chemistry, he said.

"It saves us a lot of headaches not having to worry about that toxin breaking through," he said, pointing out the public has freaked out in other parts of Ohio because of the toxins.

The city's drinking water continues to meet Ohio EPA standards for trihalomethanes; chlorine, an additive used to control microbes; nitrate, a runoff from fertilizer use; and haloacetic acids, a byproduct of drinking water disinfection.

"Things change as science evolves," Sudman said. "They come up with new things to test for and new methods, and you're going to find stuff as those new methods come out."

The 2012 annual report showed detected contaminants in the city's drinking water are below maximum levels allowed. The U.S. EPA regulates more than 80 contaminants in drinking water.

The EPA years ago ordered Celina to lower the THMs level in its drinking water. Organic material in the water had been reacting with chlorine to form THMs, which lab tests have linked to some forms of cancer and other diseases.

The city in 2008 added a $6 million water treatment facility - equipped with eight carbon tanks - that adds granular activated carbon filtration to the treatment process to stop the formation of THMs.

"Since the construction of the ... facility, the city not only has met (and exceeded) OEPA drinking water safety requirements, we continue to do so today in spite of the lake algae, continually changing water temperature and conditions," Hazel said. "We've always remained in compliance since the facility went online and the recent efforts at controlling algae toxins with alum, treatment trains, etc."

The city recently solicited new carbon bids and will pay $265,000 for a year's supply, Sudman said. Previously, the city paid $320,000 a year.

"In the beginning, we chose the more cost-effective method of regenerating our own carbon with the addition of approximately 10 percent virgin material," Hazel said. "This way we keep costs down while being assured of the correct carbon design."

Though Celina's drinking water is safe - and its taste and odor dramatically improved the last several years - some people still won't consume it, Sudman said.

"We've had a history of bad water here for aeons," he said. "We have a lot of customers (that) even though the water's perfectly safe now, they've grown up here so they just don't drink the water."

- The Associated Press contributed to this story.

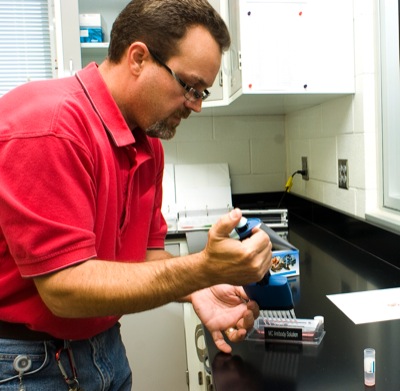

Photo by Mark Pummell/The Daily Standard

Algae toxins are removed with potassium permanganate, alum polymer and other chemicals at the Celina water treatment plant.