Wednesday, December 26th, 2018

Drug users offered help

Team gives information on treatment programs

By William Kincaid

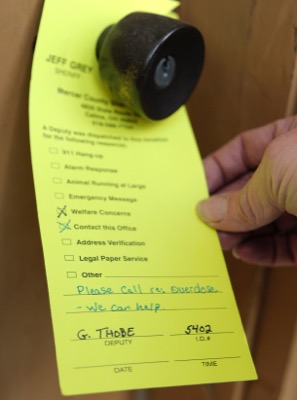

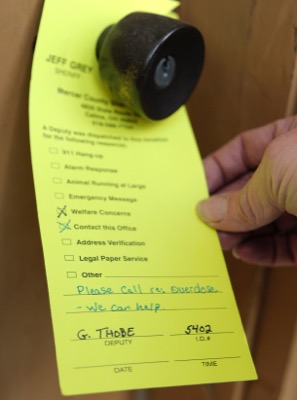

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

The Mercer County Quick Response Team tries to contact residents who have recently overdosed on drugs, offering them information on how to sign up for treatment. If no one answers the door, team members leave a yellow door hanger asking them to call the team for help.

CELINA - Mercer County Sheriff's Chief Deputy Gery Thobe every week or so ambles up to and knocks on the door of a drug user's residence, not necessarily as a law enforcement officer but as a concerned member of the community offering a helping hand.

Dressed in plain clothes and accompanied by a Foundations Behavioral Health Services drug/alcohol counselor and Mercer County Emergency Medical Services member, Thobe tries to persuade residents who have recently overdosed on opiates to seek detox, treatment and recovery services.

"When we go there we don't speak to them about any arrests or any charges," Thobe told the newspaper. "We don't talk about the criminal case portion of it at all because I don't want people thinking we're going to come to the door and arrest them because they didn't do what we wanted."

Rather, the Quick Response Team offers to help the drug user get clean by enrolling in treatment programs and support group meetings.

Under Ohio House Bill 110, people who overdose can escape formal charges if they pursue treatment within 30 days of the incident. Also, state law allows officers access to EMS records of those who have recived Narcan, which reverses the effects of opioid overdoses, sheriff Jeff Grey pointed out.

The Quick Response Team then springs into action, visiting the home of those who have recently overdosed. They come with a pamphlet and other information about how to access treatment services and support services. They also offer details about financial assistance available to those who don't have insurance or are indigent.

Thobe said about three-quarters of the people to whom they speak are receptive.

"Some won't answer the door because they know it's the cops. We leave a door hanger (listing the purpose of the visit) and normally they'll call," Thobe said.

It's difficult to discern just how many people contacted by the team follow through with its recommendations, Thobe said, noting sometimes he hears directly from people who have entered treatment.

"I know there are success stories out there. I know there are many more that are not success stories, but I don't track who does and who doesn't because that's not the purpose of it. The purpose of it's just to get them the help," Thobe said.

The team made 44 visits in 2017 and 22 so far this year. The decline in visits is likely indicative of a decline in heroin use but an uptick in methamphetamine since Narcan is administered only for opioid overdoses.

"They say that people are more likely to agree to treatment if you get to them within the first seven to 10 days," Grey noted.

"If it's fresh in their memory they're more likely to agree to treatment," Thobe added. "A majority of these people will not argue with you. They'll tell you flatly, 'Yes, I overdosed.' "

Also, by acting quickly, the team has a better chance of reaching transient drug users who are prone to moving on quickly to other places of residence.

While some respond to the team's offers with gratitude, others may flat out turn down the team's entreaties.

"The very first person that I spoke to in this program was a young lady from Celina, and she refused assistance," Thobe said.

She wouldn't answer the door so the team left a hanger on the door. She did, though, make a phone call to Thobe.

"Her comment to me was, 'I'm not interested in getting help. This is my lifestyle right now and I know that there's a very good possibility that it's going to kill me, but I'm not ready to get assistance yet,' " Thobe said.

Not long after the call, she overdosed and died, he said.

"A lot of the obstacles, I think, are probably their lifestyle and the people that they hang around with," Thobe said when asked why some are reluctant to get help.

Having been on the Quick Response Team now for two and one-half years, Thobe said he doesn't know if it can be made more effective.

"You can't force people to sign up for treatment," he said "The only thing we can do is keep offering them whatever is available to us, which, right now, Foundations is the most promising for us."

Grey said the Quick Response Team's ultimate goal is to demonstrate that even though the sheriff's office officials make drug-related arrests, their ultimate goal is to get people off drugs and on to leading productive lives.

"The ones that would like to get out of the lifestyle and that are struggling, I think some of them think that people don't care, and hopefully by having this program they realize that we do care," Grey reflected.

Grey said it took him a while to understand that willpower alone is not enough to overcome drug addiction. Those who have freed themselves from its grips and turned the corner deserve a huge pat on the back, he noted.

"I really believe that some of them are trying to get their life going in the right direction and they're just not strong enough," Grey said. "People that don't think that (drug addicts) can just get out of bed in the morning and go, 'I'm never going to use again,' don't understand the addiction. There are very few people who can do that without help."

The Quick Response Team was founded in July 2016, at the peak of the local heroin epidemic, after sheriff's office personnel studied similar programs in larger Ohio counties.

"We can't do everything they do because we're not that big, but what parts can we do?" Grey noted.

Thobe said he didn't come into the Quick Response Team with the naive assumption he was going to save the world.

"If we can get two of these people to go through rehab and not go through what they've done (again), then it was worth the effort and time," he said.