Monday, February 1st, 2021

Local jail escapes worst of COVID-19 pandemic

By Leslie Gartrell

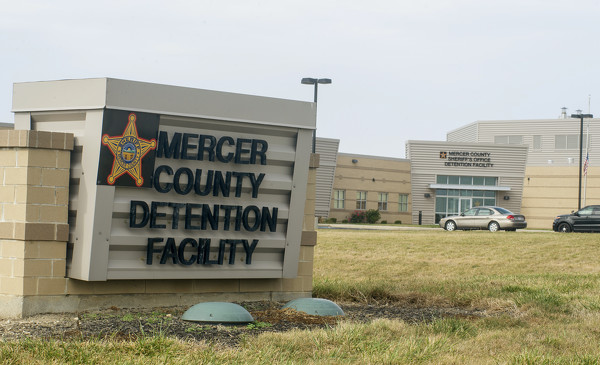

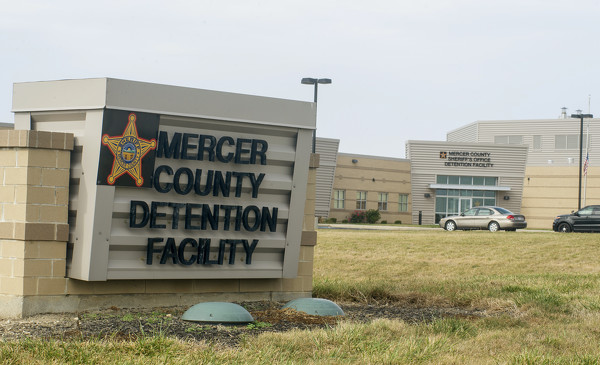

File Photo/The Daily Standard

Jails and prisons have been COVID-19 hotspots throughout the pandemic. In Ohio, over 7,200 incarcerated people have tested positive for COVID-19, but only one incarcerated individual at the Mercer County jail has tested positive thanks to protocols put in place.

CELINA - Jails and prison systems throughout America have been recurring hotspots for COVID-19 outbreaks since the pandemic began.

The Mercer County jail isn't one of them.

Since the beginning of the pandemic, only one incarcerated person has tested positive, and only six of the 75-strong staff at the Mercer County Sheriff's office have tested positive.

Sheriff Jeff Grey said the jail and sheriff's department as a whole has remained relatively unscathed thanks to their nursing staff.

"Once we realized it was serious, we put the nursing department in charge," Grey said in an interview on Wednesday.

Megan Fokine, one of two nursing staff at the jail, said the jail's success can be attributed to following hospital protocol.

"We follow the same precautions as a hospital would," she said.

Staff were limited to their own departments to prevent the spread between divisions. Before a mask mandate ever went into effect, staff had to wear a clean, cloth mask while they were inside the facility and return them at the end of the day to be sanitized.

Employees had their temperatures taken every day and answer questions about symptoms.

"If someone had a sniffle, we'd send them home," she said.

Staff also sanitized their work spaces when they got in and again when they would leave for the day, ensuring every shift was sanitized.

The sheriff's department closed the lobby in April, except for conceal carry permit applications and background checks. It re-opened in August only to close again in November as cases reached a fever-pitch in the county. Now, the department plans to reopen the lobby once again today.

Employees still have their temperatures checked daily, and they also still wear masks and sanitize frequently. If a staff member doesn't feel well, they report directly to Fokine. If a family member or significant other doesn't feel well, staff also report that information to Fokine to prevent asymptomatic spread.

Throughout the course of the past 11 months, Fokine said she sends routine emails to employees reminding them to keep up the work and not let up.

Grey said the only safety precaution that's been optional for staff is getting the COVID-19 vaccine. However, Fokine said many employees have shown interest in getting vaccinated. About a third of the department's staff have been vaccinated.

Fokine said the department was blessed to have personal protective equipment before the pandemic gripped the state. When it did become difficult to acquire PPE due to backorders or shortages, Fokine said they were further blessed by local organizations who donated cloth masks or hand sanitizer.

The Mercer County facility is one of few success stories of jail or prison systems escaping COVID-19 outbreaks.

As of Friday night, over 7,200 incarcerated people in Ohio have tested positive, and 132 have died, according to the COVID Prison Project, a public database of COVID-19 within U.S. correctional facilities. More than 4,400 staff at jails and prisons in the state have tested positive, and nine have died.

Nationwide, more than 372,000 incarcerated people have tested positive, and nearly 2,300 incarcerated individuals have died. More than 89,000 staff working in prisons have contracted the virus, and 142 have died.

And while it soon became obvious that many jails and prisons were becoming virus hotspots, less obvious was the fact that correctional institutions had become vectors of the virus and contributed to spread throughout communities and nearby areas.

According to the Prison Policy Initiative, a study on mass incarceration, COVID-19 and community spread found that prisons and jails were linked to an additional 566,804 COVID-19 cases in the U.S. from May 1-Aug. 1, 2020. The Marion Correction Institution of Marion County, Ohio, served as an example.

Marion Correction Institution was the site of one of the largest outbreaks of COVID-19 in the U.S., according to the Prison Policy Initiative. And the study estimated incarceration within Marion County was responsible for an additional 310 cases in the county between May 1-Aug. 1, 2020, or 37% of the county's total cases during that period.

Mercer County jail chief deputy of corrections Jodie Lange said the best way staff keep their inmates safe from COVID-19 is to prevent it from transmitting in the first place.

The first step was lowering the jail population. The Mercer County jail typically houses 80 inmates at a given time, according to Lange. Before the pandemic, the jail would contract with other jails and accept out-of-county inmates from facilities that lacked the space.

Once the pandemic set in, the jail stopped taking out-of-county inmates. If people incarcerated in the jail weren't from Mercer County, they were sent back to their respective county jail. The only other jail they would accept inmates from was the Auglaize County jail, Lange said.

As a result, the incarcerated population at the jail has been around 50-55 people in the last few months. No inmates were released to lessen the population, Lange said.

The average length of stay for a person incarcerated at the jail is roughly 55 days, Lange said, although there is also a notable amount of stays that last 180 days.

Grey said the department has worked with the courts and arranged video arraignments for inmates, which has greatly reduced transportation.

Working remotely also has had some benefits, Lange said. The department has been able to offer telepsych appointments for the incarcerated population, which has been a welcome addition.

"It's been nice because (telepsych officials) can see more people, and it's reduced transportation," Lange said.

When someone is brought into the jail, they are given a mask, have their temperature taken, answer screening questions and are checked for COVID-19 symptoms. Those factors determine where they are housed, Lange said.

If a person says they have COVID-19 or they have symptoms, Lange said the department can check with the Mercer County Health District to see if that person has actually tested positive or been in contact with someone who has.

Regardless, Fokine said staff follow hospital protocol and treat the inmate like they have COVID-19 by medically separating them from the rest of the population.

Treating an inmate as though they have COVID-19 has been critical at preventing the spread. The lone inmate who had COVID-19 had symptoms and was immediately separated.

Fokine said the jail is equipped to medically treat their incarcerated population similar to other medical facilities, although the inmate who tested positive was later hospitalized.

While inmates are not required to wear masks, correctional staff always wear them, Fokine said. Lange noted inmate workers have to wear masks while they do their jobs and are given fresh masks each time they work.

Lange added the inmates ability to work hasn't really changed over the course of the pandemic and has largely remained the same.

People incarcerated at the jail have their temperatures taken daily. Fokine noted the incarcerated population doesn't have access to the same media or resources as non-incarcerated individuals, so she and other staff try to keep them informed and educated about the virus.

If a person does exhibit symptoms, they're moved to a quarantine dorm. Fokine said someone who is detoxing can have similar symptoms to a person with COVID-19, which is where hospital protocol comes in.

Lange said one of the downsides is that an inmate's stay in the quarantine dorm may be longer than necessary.

For example, if an inmate in the quarantine dorm is almost done with their quarantine period and another inmate is introduced to the dorm, the first person's stay in the dorm will be extended because they have to start the quarantine process all over again.

Lange also said the pandemic has resulted in the jail housing some inmates longer than usual.

As vaccine availability begins to widen, the discussion of whether incarcerated people should be prioritized as a high-risk population has emerged at the forefront.

"We deal with the most broken people, and probably some of the sickest people in the county," Lange said. "They're not the healthiest population… they definitely fall into the high risk category."

Fokine said the incarcerated population is similar to nursing homes or other long-term care facilities where there's a high risk of spread.

"No matter who you are, where you are, or what status you are, everyone's a human being," Fokine said. "Even though they've done a crime, everyone's made a mistake in their life… that doesn't mean that they should not get medical care. They have a right to medical care just as well as anyone on the street."