Wednesday, June 16th, 2021

A Belated Bicentennial

Pandemic delayed Rockford celebration

By Leslie Gartrell

Photo by Dan Melograna/The Daily Standard

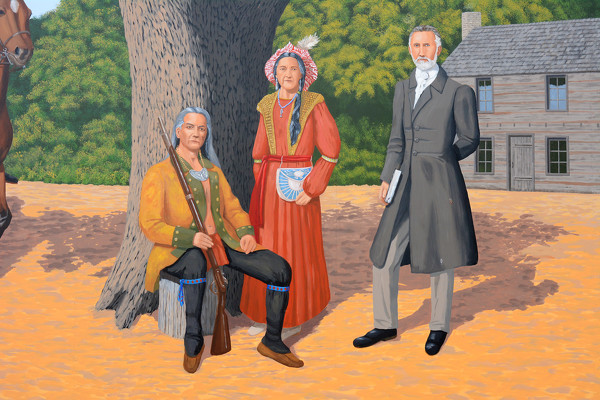

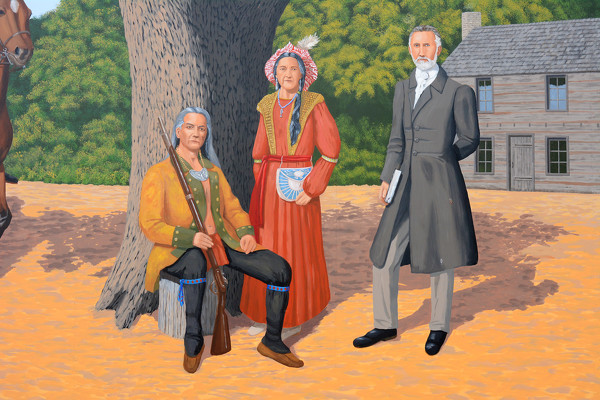

A mural of Anthony Shane, from left, his wife Lamateshe and the Rev. Isaac McCoy is located on the south side of the Rockford Fire Department. Artist Daniel Keyes consulted with local historian Harrison Frech to help paint the mural to mark the village's bicentennial.

ROCKFORD - Mercer County's oldest village wasn't always known as Rockford.

As the village celebrates its belated 200th anniversary delayed by the COVID-19 pandemic and prepares for the Rockford Community Days celebration this weekend, residents can look back to the village's original founding as Shanesville.

The village was founded in 1820 by Anthony Shane, a scout, messenger, interpreter and entrepreneur who served in multiple battles throughout his life and in the War of 1812, according to local historian and author Harrison Frech.

"He had a very eventful life," Frech said of Shane. "He was considered rich by (many) standards, a successful farmer, and a man who gave almost 40 years to the United States government as an interpreter and scout."

Shane's service in the War of 1812, his leadership of the local Native American population and his willingness to use his knowledge of Native American culture and local history to aid new settlers ingratiated him to the growing white population of the area, Frech said.

According to Frech's book "Anthony Shane, Metis Interpreter: A Bridge between Two Cultures; Scout, Interpreter, Town Founder, Witness to History," Shane was born Antoine Chene, a family name that means "oak," around 1773 in what is now Defiance. His father was French-Canadian and his mother was a part of the Ottawa tribe.

Shane was a Metis, or a person with mixed Native American and European ancestry. As a Metis, Shane faced particular challenges in the racially divided society of the period. Growing up with a Native American family led Shane to master at least five indigenous languages as well as French and English.

Four generations of Chenes would be interpreters, according to Frech. Shane's father was an interpreter and trader, a trait which stayed with Shane as he later became an interpreter and entrepreneur himself.

Shane worked as an interpreter for various governments throughout his life. He was a member of a British-Canadian force in the early 1790s that supported the Western Confederacy of Native Americans, a coalition of tribes that united to attack American forces. He also fought in the 1791 Battle of the Wabash, or St. Clair's Defeat.

He later took an active role opposing a new American Army led by Anthony Wayne in 1794 and fought in the Battle of Fallen Timbers, the last major conflict of the Northwest Territory Indian War between Native Americans and the United States.

Less than seven months after the Battle of Fallen Timbers, Shane entered the service of the U.S. in 1795 as an interpreter at Fort Defiance. Shane at this time anglicized his name from Antoine Chene to Anthony Shane, which Frech noted is similar to Anthony Wayne. Shane likely realized the new United States would become a dominant force, and anglicizing his name would offer him the best opportunity for survival and success, Frech said.

In the period leading up to the War of 1812, Shane was intermittently employed by the Army and local Native American agents as an interpreter, messenger and intelligence gatherer. He was especially involved in the War of 1812, serving as a spy, scout, guide, interpreter and leader throughout his service, according to Frech.

The Metis were often resented by Americans for their preferred culture and dress of the French creole and local Native American over American culture, according to Frech. Lewis Cass, future governor of the Michigan Territory, U.S. senator, 1848 Democratic presidential candidate and associate of Shane's, even expressed that the Metis "must learn new ways or be removed."

Yet despite being Metis and his earlier support of the British, Shane was lauded as a war hero and rewarded by the U.S. government for his loyalty and service. In 1815, he received a land grant from Congress for "valuable and honorable service during the last war." The 320-acre grant was at the second crossing of the St. Marys River on the south side, which was dubbed Shane's Crossing.

Shane also served as an interpreter in the negotiations for the treaties of Fort Meigs and St. Mary's in 1817-1818. In addition to the pay of $1 per day, he received a 640-acre reserve on the north side of the St. Marys river across from his first land grant.

Rockford got its start with certain advantages, Frech said. Commerce grew along the river as goods were transported from St. Marys to Fort Wayne, Indiana, and the area had rich farmland. With good land and an opportunity for growth in sight, Shane used his land grants to fuel a real estate enterprise and platted Shanesville in June of 1820, the first platted town in Mercer County.

Shanesville started with 42 lots and grew slowly at first due to its swampy environment. New roads had to be built to allow for travel over muddy paths, and the land had to be drained to keep away mosquitoes and the malaria they carried.

As the village grew, the town became Shane's empire as he ran a tavern, trading post and ferry. On the ferry ride, settlers would pass Shane's Reserve and Shane's home, a double log cabin by his farm where he and his wife, Lamateshe, raised a multitude of vegetables.

Shanesville was incorporated as Shanes Crossing in 1866, as another Shanesville in Ohio had been founded in 1814. Although the town had already gone through a name change, the townspeople wanted to change the name again in 1889-1890 because they believed Shane's Crossing was "too frontier," according to Frech. The townspeople voted to change the name to Lacine.

Interestingly, Frech noted the post office, for one reason or another, didn't accept Lacine as the new name and instead chose Rockford, which came in second place. Rockford came from the term rocky ford, which is the low point in a river.

The village's founding family was non-traditional by some standards. Both Shane and Lamateshe had prior marital relationships, each with their own children. Shane had at least one son before his marriage to Lamateshe, and she had at least one son and two daughters before she was widowed.

The couple cared for each other and were very supportive of one another, Frech said. Shane protected Lamateshe's rights in the white world by getting a civil marriage on Dec. 14, 1822. The family's land documents would include both their names, with Shane's signature and Lamateshe's mark. The family later migrated to Kansas in the mid- to late-1820s, where Shane continued to work as an interpreter until his death in 1834 at Fort Leavenworth.