Tuesday, March 22nd, 2022

Running for cover

Cover crops, no-till good for land, pocketbook

By Leslie Gartrell

Submitted Photo

Luke VanTilburg plants corn into a growing cover crop mix of cereal rye, annual rye, hairy vetch, rapeseed and clover in this 2020 submitted photo.

Luke VanTilburg and his family have used cover crops and no-till on their 4,200-acre farm since about 2008.

The family had been using conventional tillage practices until that time and began to wonder if there was another, better way to do things, VanTilburg said.

They started with strip till and cover crops as a stepping stone, VanTilburg said. Strip tillage works about a 5-inch-wide row of soil as opposed to tilling the whole field.

After four or five years, the VanTilburgs moved to no-till in combination with planting cover crops. In the years since, VanTilburg said the difference in soil health has been incredible.

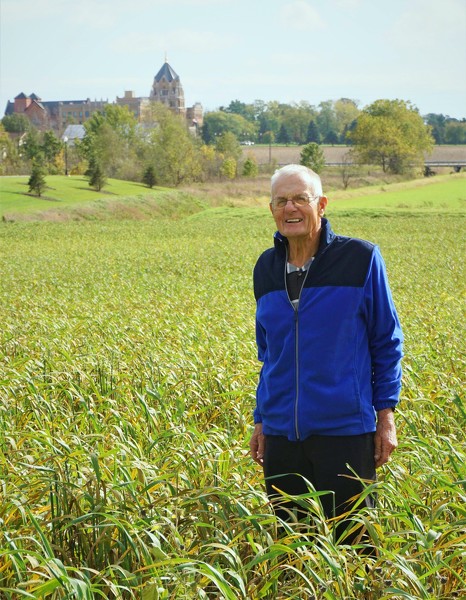

Photo by Paige Sutter/The Daily Standard

Luke vanTilburg points out leftover crops from the previous harvest season.

"It's amazing, the difference that (no-till and cover crops) has made in soil health," he said. "The texture of the soil, the crumbliness of the soil, the earthworm activity is huge. It's amazing how much more the ground is able to handle water events, and you can still get back out in the field and get things done."

Now in a partnership with the McCarty family, the fourth generation of VanTilburgs provide their non-GMO crops to feed the 4,500 cows at MVP Dairy near Celina.

Slowly but surely, more area farmers have incorporated cover crops in combination with no-till into their operations since the push began about 15 years ago.

Jim Hoorman, consultant and former OSU Extension agent for Mercer County, was hired by Mercer County in August 2009 mostly to encourage Grand Lake watershed farmers to plant winter cover crops and promote good manure management practices that reduce phosphorous runoff into the 13,500-acre lake.

As the name suggests, cover crops are crops that "cover" the soil. Winter cover crops have been shown to reduce soil erosion and nitrogen leaching, suppress weeds and pests and increase soil organic matter, according to the American Society of Agronomy.

Winter cover crops are planted shortly before or soon after harvest of the main grain crop and are killed before or soon after planning of the next grain crop, according to the American Society of Agronomy.

Hoorman, an expert on cover crops, said the push was made to educate watershed farmers about the practices due to Grand Lake's poor water quality, which is largely due to agricultural runoff.

Grand Lake has been plagued by toxic blue-green algae blooms and state-issued water advisories for over a decade. The algae is fed largely by phosphorous that runs off mostly farmland, the largest land use in the livestock rich, 58,000-acre watershed area that drains into the lake.

The Midwest agricultural landscape is typically green for only half of the year, Hoorman said, with no living cover for the other six months. The goal of cover crops is to have something green growing for as close to 12 months out of the year as possible, he said.

"We're reestablishing Mother Nature's natural cycle," Hoorman said. "Cover crops is one way to re-establish some of those natural cycles."

VanTilburg and Hoorman said the environment created by cover crops and no-till is similar to prairies, which are grasslands that grow year-round.

"The 1930's drought (Dust Bowl) was exasperated by the elimination of prairies and grasses because microbes on (plant) leaves evaporate and turn into rain," Hoorman explained. "So if you have plants growing year round, that means there are more microbes in the atmosphere, which evens out the rain cycle."

Microbes are tiny living things that are too small to be seen by the naked eye, according to the U.S. National Library of Medicine. They live in water, soil and in the air. The human body is home to millions of these microbes too, also called microorganisms.

Cover crops provide a litany of benefits for farmers, Hoorman said. Cover crops enhance biological life, nutrient cycling from the soil into crops, increase soil organic matter, improve water infiltration and storage, improve soil structure and protect soils from eroding, he said.

Increased organic matter is huge, Hoorman said. Organic means it came from living matter and contains carbon while inorganic means molecules that lack carbon, Hoorman explained.

Soil organic matter has two major groups, according to information from Hoorman's consulting business, Hoorman Soil Health Services -the humus, or long-term decomposed stable organic matter, and the active organic matter which is easily decomposed and unstable. Generally, it's the active organic matter which is lacking in degraded soils, he said.

Microbes are an important part of soil health and organic matter, Hoorman said, and about 60% of the microbes that live in soil are dormant.

"Whenever you have live roots, you have about 1,000 to 2,000 more microbes (compared to bare soil), and each one becomes a mini bag of fertilizer," he said.

The roots of cover crops dig into the soil, breaking up compacted soil and reviving microbes, Hoorman said.

Michael Watercutter, Mercer Soil and Water Conservation District administrator, said his family has used no-till on their 300-acre Shelby County farm since 2018. They have used cover crops on and off again for about six years, with the last three years planting cover crops consistently.

Watercutter said since starting the practices, their soil organic matter has increased by nearly 1%. While that may not sound like much to the everyday layman, Watercutter said it's a significant improvement.

"The water holding capacity is higher," he said. "We're now having these short drought periods (in the summer), so it's (the soil) better for the climate we're heading to."

Healthier soil also welcomes critters such as earthworms, which promote beneficial fungus and bacteria growth, reduce soil compaction through tunneling, increase water infiltration and fertilize the soil, according to OSU Extension.

VanTilburg said the change in earthworm activity on their farmland has been huge since adopting no-till and cover crops, which he said has been "amazing" for the soil.

Different cover crops provide different soil health benefits. Legumes such as clovers, hairy vetch and field peas can add substantial amounts of available nitrogen to the soil, according to the Ohio State University Extension.

Non-legumes such as rye, oats and radishes can be used to take up excess nitrogen from previous crops and recycle the nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium to the following crop, according to OSU Extension. This is very important after manure application because cover crops can reduce leaching of nutrients into water sources, Hoorman said.

Watercutter said his family uses a variety of cover crops, planting a six-way or eight-way blend of cover crops depending on what cash crop is going on the field.

The mix the Watercutters plant before wheat typically consists of winter barley, cowpeas, Austrian winter peas, radishes, sunflowers, crimson clover, rapeseed and sun hemp, he said. Watercutter said they also plant cereal rye into growing corn before beans for the next year.

Photo by Paige Sutter/The Daily Standard

Luke VanTilburg of MVP Dairy examines dirt in one of his fields in which he practices no-till farming.

VanTilburg said his family also uses a mix of winter cover crops, including cereal and annual rye, radishes, clover, rapeseed, hairy vetch and tritcale.

"Some act like tilling, others hold and release nutrients, some help with weed control, some create nitrogen," VanTilburg said. "Each species has a specific job."

Another benefit to using cover crops and no-till is decreased soil compaction, increased soil porosity and improved soil structure, Hoorman said.

Soil structure improvements may take three to five years to see a difference, he said. However, Hoorman noted the changes will be more permanent with cover crops than conventional tillage, which reduces soil organic matter and worsens soil structure.

In the last 100 years, tillage has decreased soil organic matter levels by 60% to 70%, according to the American Society of Agronomy.

Another major benefit cover crops and no-till practices provide is increased soil stability, Hoorman said. Stable soil can handle major rain events better than tilled soil, and farmers can even get out in the field earlier to plant.

"Conventional soil is squishy when wet and hard as a rock when dry. If you use no-till and cover crops, your soils have more structural stability, so you can plant on your fields five to 10 days earlier in the spring."

Garrett Hellwarth, a Hopewell Township dairy farmer who operates a 200-head dairy, has used cover crops and no-till on his land for 10 years since he was introduced to the practices by Hoorman.

Hellwarth said he primarily grows sorghum-sudangrass as a cover crop after planting wheat to use as forage. The sorghum-sudangrass makes for excellent feed, he said, and he often can grow his own cover crop seed to save on seed costs.

"With a dairy farm, it's a win-win," he said. "The soil always stays intact, the plants keep spring rain. It's real win-win, seeing the erosion it prevents, especially with these spring rains."

After cover crops are planted, Hoorman estimated 90% of farmers kill them off. Most cover crops are killed with herbicide or burned, he said. Other farmers plant into their cover crops green, according to Hoorman.

Planting green means a farmer plants a cash crop into a still-green cover crop, Hoorman explained. For example, VanTilburg said he uses a roller crimper, which snaps the tall cover crop stalks. The cover crops are then left on the field.

"It creates a mat to hold moisture, kind of like mulch," VanTilburg said. "It's a layer of protection."

Hoorman said many farmers were hesitant to try using cover crops and no-till practices when he first pitched the idea in the late 2000s.

"We were probably 10 years ahead of our time," Hoorman said. "It was a tough sell, especially with manure."

Hoorman said the biggest issue at the time was manure incorporation. Producers with livestock operations in the Grand Lake Watershed with a certain number of animals must have nutrient management plans which lay out how much manure will be applied to fields.

Dairy and hog manure can't be easily transported due to the high water content of the manure, Hoorman said, so many farmers apply dairy and hog manure to their fields to get rid of it. Poultry manure can be more easily and affordably transported because it is drier, he said.

For producers in the Grand Lake watershed, manure has to be incorporated into a field within 24 hours of application. Most farmers till to incorporate manure, Hoorman said.

"So if you want to put cover crops on (the field), you basically had to till it," Hoorman said. "Farmers who wanted want to put manure on their fields had a good excuse not to use cover crops."

One of the other hurdles of no-till is the potential loss in yield in the first few years after starting, according to Hoorman.

In many situations, yields drops slightly after switching to no-till, according to information provided by Hoorman Soil Health Services. However, cover crops with no-till have the ability to jump-start no-till and improve soil health, which perhaps reduces or eliminates any yield decrease.

Aside from improvements to soil health, there is also an economic benefit to cover crops.

The economics of using cover crops can be calculated by the savings of purchased nutrients and herbicides versus the additional cost of using cover crops, according to OSU Extension.

As the cost of fertilizer and herbicides continues to increase, Watercutter said the benefits of using cover crops in a sustainable farming system can be attractive to modern farmers.

Watercutter said his family saves money on fuel because they utilize no-till in their farm operation. He estimated they save roughly $40 an acre on fuel because they don't have to till much land. No-till also extends the life of equipment and saves time, he said.

While adopting cover crops and no-till practices have many benefits, the farmers and Hoorman agreed it requires a willingness to learn and patience.

"It takes time," Hellwarth said. "When to plant, when to kill. There are some variables and you typically need to act more quickly, which can present challenges in the spring. But challenges can be fun."

Watercutter suggested farmers start with an easier cover crop, such as planting cereal rye into corn stubble. Many farmers use one or two varieties of seeds, but Watercutter said a high variety seed mix is a good option to build soil health and organic matter quickly.

VanTilburg said his family adopted cover crops and no-till when the USDA's Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) was introduced.

Commodity market prices were also high, he said, so the family didn't have as big of a risk adopting the practices.

"The good thing is that for today's farmers, hay crop prices are back up again, there's the H2Ohio program that can provide incentive to try cover crops," VanTilburg said. "It's another great time to dip their toes in the water."

Matt Heckler, Mercer Soil and Water Conservation District technician, said he believes there has been an increase in farmers taking up no-till and cover crop practices since the push began 15 years ago. However, Heckler said participation depends on the incentives for farmers.

Programs that offer to compensate farmers for adopting conservation practices, such as Ohio's H2Ohio program, have drawn broad participation from farmers. In September, SWCD board of supervisors approved 115 H2Ohio contracts, totaling nearly $4.1 million in state funds.

Launched in 2019 by Gov. Mike DeWine, the H2Ohio program was created to fund investments in 10 scientifically proven interventions aimed at reducing agricultural nutrient runoff in an effort to decrease toxic algal blooms in Lake Erie. The program also funds projects that create wetlands, address failing septic systems and prevent lead contamination.

VanTilburg said there are different ways to farm for each farmer, and no way is necessarily right or wrong. Adopting cover crops and no-till practices was the right choice for their operation, he said.

"We try to do what's right for us and for the world we live in," VanTilburg said. "Try to keep moving forward, try to do those things for the next generation. We've got the fifth generation coming, and we want to leave (the land) in better condition than we found it in."