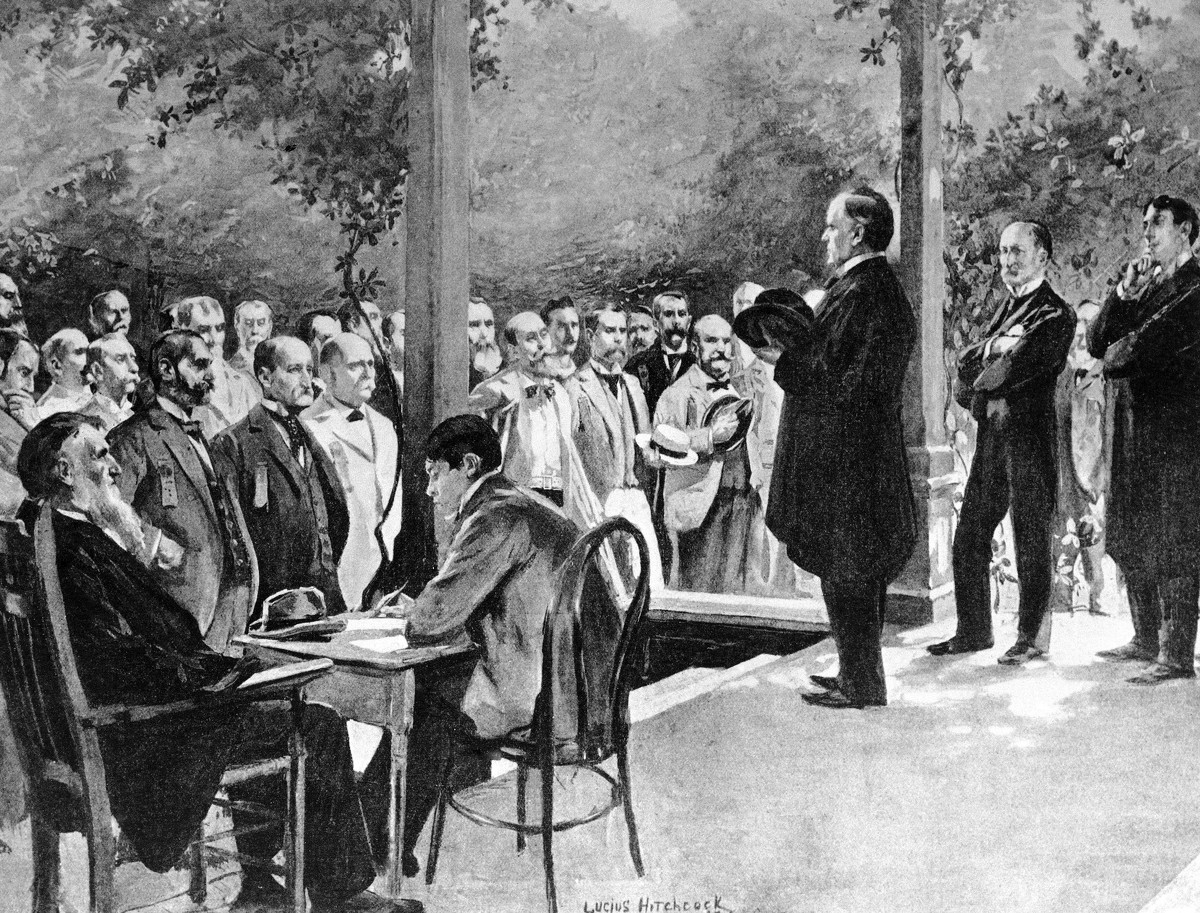

This drawing shows Major William McKinley, the presidential nominee for the Republican Party, make an elaborate front-porch campaign speech at his home in Canton, Ohio in 1896. In the nation's early decades, campaigning for oneself simply wasn't done. It was seen as rude and uncivil. But three Ohio-born presidents, beginning with James Garfield in 1880, found a clever way to sidestep tradition. They stumped from their front porches. (AP Photo, File)

MENTOR, Ohio (AP) - Both Donald Trump and Joe Biden are wrestling with how to campaign safely during the coronavirus pandemic. Historians offer up precedent that might come with some lessons: James Garfield let the people come to him.

From the front porch of his Ohio home, the 19th century presidential candidate hosted thousands of people on his shady lawn to hear him talk about his plans. His at-home experiment proved successful in 1880. It was copied by Oval Office successors, made famous by William McKinley some 16 years later and left a lasting imprint on presidential politics - all while keeping White House hopefuls relatively safe from disease.

"It's 1880. They can't follow him on Twitter or look at his Facebook page or see him on CNN every night," said Todd Arrington, site manager of the James A. Garfield National Historic Site. "Candidates were expected to basically stay home and really not say anything. So when people started showing up here, Garfield did kind of break the mold."

The mold has broken again, thanks to the coronavirus, which essentially has frozen traditional campaigning. But on Saturday in Tulsa, Oklahoma, Trump is planning to restart his raucous rallies, a decision drawing sharp warnings from health officials. Presumptive Democratic nominee Biden has begun to make some public appearances but is still largely focusing his appearances online.

The front porch of the James A. Garfield National Historic site is shown, Wednesday, June 3, 2020, in Mentor, Ohio. Once upon a time, all U.S. presidential candidates were stuck at home. Infectious diseases, like the one preventing traditional campaigning so far this year by Donald Trump and Joe Biden, were only one reason. In the nation's early decades, campaigning for oneself simply wasn't done. It was seen as rude and uncivil. (AP Photo/Tony Dejak)

Garfield wasn't necessarily seeking attention when crowds began traveling to his farm, named Lawnfield, in northeast Ohio. The little-known congressman had been selected on the 36th ballot during a disputed convention and people were curious about the mystery candidate. They started traveling from nearby cities - Cleveland and Youngstown - and by train from neighboring states. Some people, accompanied by marching bands, pranced up Mentor Avenue.

Campaigning was seen as a rude and uncivil form of self-promotion at the time, and Garfield was among those who believed "the office should come to the man, not the other way around," Arrington said.

"At first Garfield really just didn't know what to do, because this was unprecedented," Arrington said. "People didn't just show up at a candidate's house."

A former Union Army general and college president, Garfield responded by strolling onto his wide front porch and talking to voters. He tailored his remarks to their issues, Arrington said. He spoke of civil rights to African American visitors, of tariffs when it was businessmen. He spoke German to German immigrants and, with female visitors, dodged the suffrage question while praising women's service during the Civil War.

Todd Arrington, site manager for the James A. Garfield National Historic Site, talks about how Garfield would speak to the public from the front porch, Wednesday, June 3, 2020, in Mentor, Ohio. In the nation's early decades, campaigning for oneself simply wasn't done. It was seen as rude and uncivil. But three Ohio-born presidents, beginning with James Garfield in 1880, found a clever way to sidestep tradition. They stumped from their front porches. (AP Photo/Tony Dejak)

The events revealed a truth about campaigning.

"The fundamental question of any campaign is how you get people out of their normal routine to participate," said Jon Grinspan, curator of political history at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History. "This is an important mechanism for answering that question. You make it an excursion. You make a day of it, you take a picnic. You get to meet the president himself and see he isn't just some person in Washington. He's one of us."

Unwittingly, this aversion to campaigning may have helped spare politicians from contagious diseases common in the day, including yellow fever, cholera and typhoid.

Candidates would not specifically have eschewed big rallies to avoid the spread of germs, Grinspan said, but it was a potential healthy side effect.

What Garfield started in 1880, other Republicans would emulate and another future Ohio president would perfect. With McKinley's 1896 campaign, the front porch campaign became a front porch strategy. Some 750,000 supporters and spectators visited McKinley's lawn in Canton, about 70 miles (113 kilometers) south of Mentor, and full-scale campaign merchandising was born.

"It's not scandalous anymore," Grinspan said. "It's gone mainstream."

This undated file photo shows six thousand people gathering to hear Warren G. Harding speak from the porch of his home in Blooming Grove, Ohio. . In the nation's early decades, campaigning for oneself simply wasn't done. It was seen as rude and uncivil. But three Ohio-born presidents, beginning with James Garfield in 1880, found a clever way to sidestep tradition. They stumped from their front porches. (AP Photo, File)

After Garfield, Benjamin Harrison (1888), McKinley, and Warren G. Harding (1920) all campaigned from their porches. All four men were Ohioans, though Harrison lived in Indianapolis when he ran, and the strategy allowed Republicans to identify themselves with the Midwest family values of the growing nation in a presidential battleground, Grinspan said.

The approach fell out of favor after Harding as cars and radio made other means of campaigning easier and wartime made stump speeches seem less wasteful. But in the age of COVID-19, echoes of Garfield's front porch strategy are apparent again.

"As quickly as things advance, they return to the basics," said Rex Elsass, an Ohio-based political strategist. "It comes down to emotionally connecting with people and convincing them you truly have a deep sensitivity to who they are and what they're about."

Today's front porch might be a phone line, a virtual event or a tele-town hall, he said - all things that have exploded during the coronavirus lockdowns.

Biden's campaign strategy against Trump might be seen as a sort of virtual front-porch campaign in itself, said retired long-time Democratic consultant Gerald Austin. Biden has started to appear in public more often, but the former vice president largely has stuck to online speeches and TV interviews in recent months.

"Where in the past front porch campaigns you wanted to have the people come to you and you didn't leave the house, now no one needs to come to you at all because of technology," said Austin, who managed Jesse Jackson's 1988 presidential campaign. "When your opponent says as many outrageous things as Donald Trump does, you just stay inside and maybe come out every once in a while. ... It's perfect. It's the best strategy they could have."

Todd Arrington, site manager for the James A. Garfield National Historic Site, talks about how Garfield would speak to the public from the front porch, Wednesday, June 3, 2020, in Mentor, Ohio. In the nation's early decades, campaigning for oneself simply wasn't done. It was seen as rude and uncivil. But three Ohio-born presidents, beginning with James Garfield in 1880, found a clever way to sidestep tradition. They stumped from their front porches. (AP Photo/Tony Dejak)

This June 3, 2020 photo shows The McKinley National Memorial in Canton, Ohio. Once upon a time, all U.S. presidential candidates were stuck at home. Infectious diseases, like the one preventing traditional campaigning so far this year by Donald Trump and Joe Biden, were only one reason. (AP Photo/Julie Smyth)